Abrams v. United States

Case Overview

CITATION

250 U.S. 616 (1919)

ARGUED ON

October 21, 22, 1919

DECIDED ON

November 10, 1919

DECIDED BY

OVERRULED (IN PART) BY

Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969)

Legal Issue

Was the application of the Sedition Act of 1918 against the defendants in this case a violation of First Amendment’s protection of the right to free of speech?

Holding

No. The defendants’ speech posed a clear and present danger to the United States’ war effort, so the government had a legitimate interest in limiting it.

Group gathered to protest the US war effort in WWI.

Background

On August 12, 1919, Hyman Rosansky was caught handing out pamphlets from a window at a hat factory in Lower Manhattan. The pamphlets, given out at a meeting the day before, had two versions: one in English, from "Revolutionists," criticized the use of American troops in the Russian Civil War; the other, in Yiddish, supported the communist faction in the Russian Revolution and criticized American weapon production for use against the communists. The police eventually caught Jacob Abrams, who made the pamphlets in his basement workshop, along with four other communist activists.

The defendants were charged under the Sedition Act of 1918 for allegedly encouraging resistance against American military actions, promoting the restriction of war materials production, and conspiring with Germany. One of the defendants died from the Spanish Flu while in custody and another was found not guilty. The remaining five defendants were found guilty in criminal court, receiving sentences from three to twenty years in prison; some would also be sent back to Russia after serving their sentences. The defendants then appealed to the United States Supreme Court, contending that their First Amendment rights had been violated.

Summary

7 — 2 decision for the United States

Abrams

United States

White

McKenna

Holmes

Brandeis

Van Devanter

Day

McReynolds

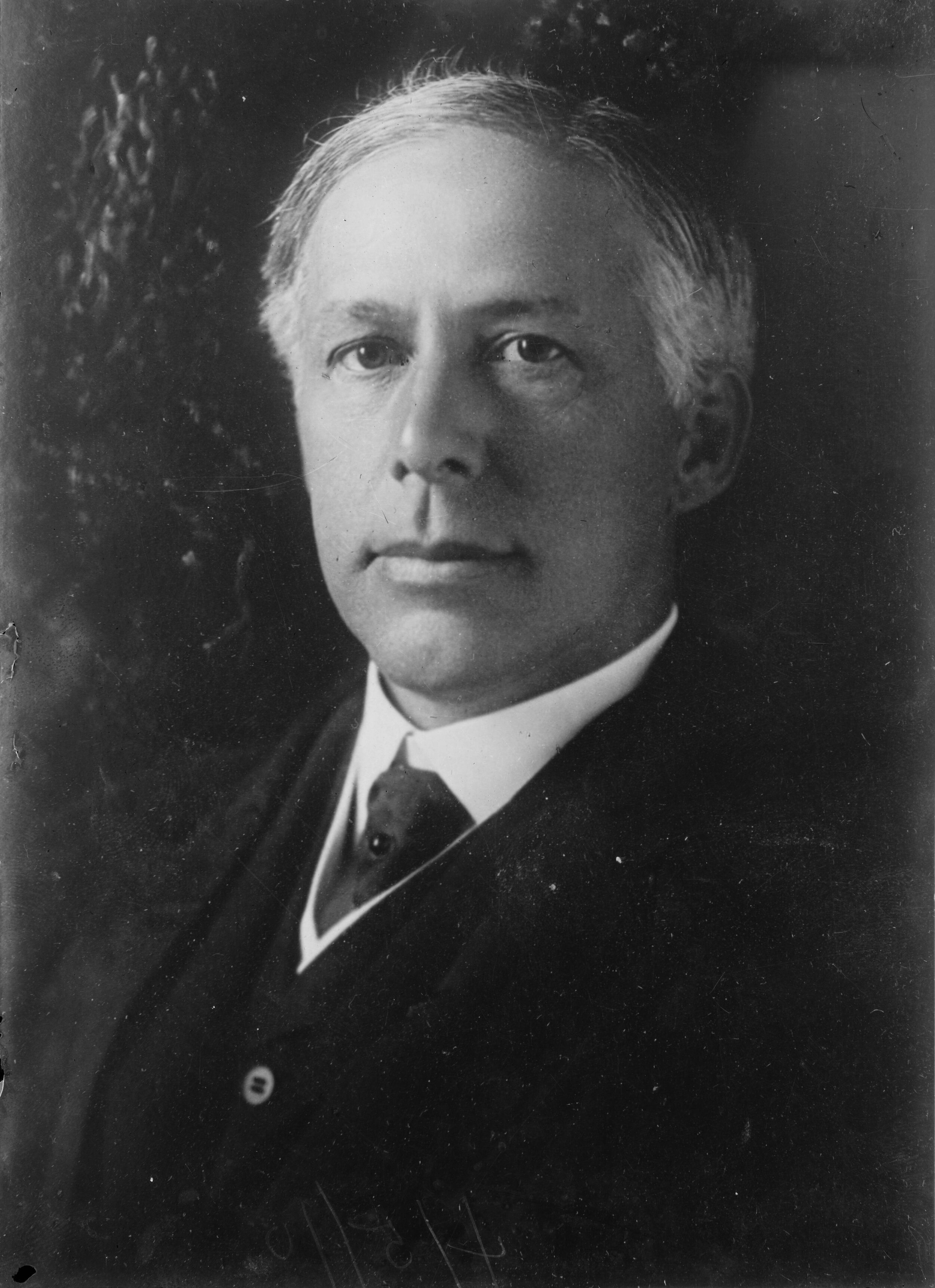

Clarke

Pitney

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Justice John Clarke reasoned that the defendants’ First Amendment rights were not violated by the Sedition Act, writing that “the plain purpose of their propaganda was to excite, at the supreme crisis of the war, disaffection, sedition, riots, and, as they hoped, revolution, in this country for the purpose of embarrassing and if possible defeating the military plans of the Government in Europe.”

In determining the purpose of the defendants’ pamphlets, Clarke found that “The essential characteristic of the pamphlets is their attempt to promote a violent revolution as a means of effecting political changes in this country,” showing the defendants' intent to provoke political change, albeit through radical means. Clarke cited the clear and present danger test established in Justice Holmes’ opinion in Schneck v. United States. In applying the test to this case, Clarke found that “. . .the manifest purpose of such a publication was to create an attempt to defeat the war plans of the Government of the United States, by bringing upon the country the paralysis of a general strike, thereby arresting the production of all munitions and other things essential to the conduct of the war.” Clarke ultimately concluded that the defendants’ speech was not protected under the First Amendment.

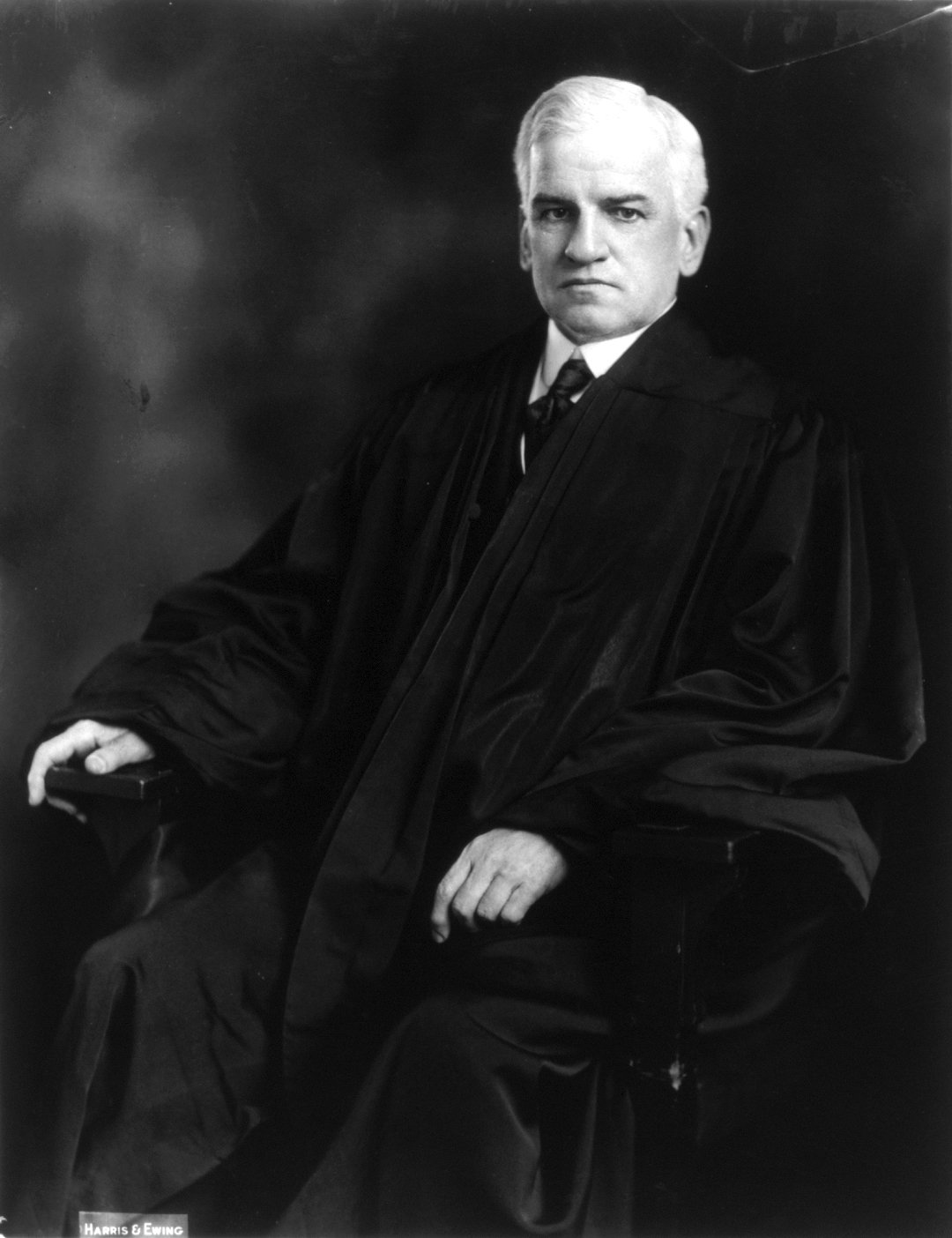

Dissenting Opinion by Justice Holmes

In his dissent, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes takes a much broader stance on the freedom of speech than Clarke, writing that “the principle of the right to free speech is always the same. It is only the present danger of immediate evil or an intent to bring it about that warrants Congress in setting a limit to the expression of opinion where private rights are not concerned.”

When Holmes applied the standards of the clear and present danger test to the defendants, he found that their speech did not rise to the level to justify government action because “nobody can suppose that the surreptitious publishing of a silly leaflet by an unknown man, without more, would present any immediate danger that its opinions would hinder the success of the government.” Additionally, Holmes believed that the twenty year sentences imposed on the defendants for “the publishing of two leaflets that I believe the defendants had as much right to publish as the Government has to publish the Constitution” was unjust. Holmes held that here was no evidence of “actual intent” to commit a crime, further suggesting that the defendants' actions did not cross the threshold of incitement to violence.

Holmes also cautioned against the dangers of censorship and the suppression of dissenting voices, warning that such measures could undermine democratic principles. He wrote, "I think that we should be eternally vigilant against attempts to check the expression of opinions that we loathe and believe to be fraught with death, unless they so imminently threaten immediate interference with the lawful and pressing purposes of the law that an immediate check is required to save the country."

Holmes' dissent articulated a strong defense of free speech rights and the importance of protecting political dissent, particularly during times of war. Holmes emphasized the need for a robust public discourse and cautioned against the dangers of government censorship and the suppression of dissenting voices, writing that “Persecution for the expression of opinions seems to me perfectly logical. If you have no doubt of your premises or your power and want a certain result with all your heart you naturally express your wishes in law.”