Central Hudson Gas & Electric v.

Public Service Commission of New York

Case Overview

CITATION

447 U.S. 557 (1980)

ARGUED ON

March 17, 1980

DECIDED ON

June 20, 1980

DECIDED BY

Legal Issue

Was the Public Service Commission’s advertising policy, which prohibited advertisements from promoting electricity use, a violation of the First Amendment?

Holding

Yes, the commission’s advertising policy violated the First Amendment.

A gas station in Portland, Oregon, June 1973 | Credit: David Falconer/Project DOCUMERICA/National Archives

Background

In 1973, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) announced its plans to enact a total oil embargo against countries that supported Israel during the Fourth Arab–Israeli War, which ultimately led to a national oil crisis. In an effort to promote conservation, the Public Service Commission of New York banned electric companies from using any language in their advertising that promoted the use of electricity. In 1976, after the nation had largely recovered from the oil crisis and the embargo had been lifted, the commission decided to continue the advertising ban. In early 1977, the commission released a policy statement banning any language contrary to current national energy conservation goals.

After the commission released its policy continuing its advertising ban, the Central Hudson Gas & Electric Company sued the commission, alleging that their First and Fourteenth Amendment rights had been violated. Both the trial court and the New York Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the commission, arguing that their interest in promoting energy conservation justified the restriction on Central Hudson’s speech.

Summary

8 — 1 decision for Central Hudson

Central Hudson

Commission

Burger

Rehnquist

Marshall

Blackmun

Powell

Stevens

Stewart

Brennan

White

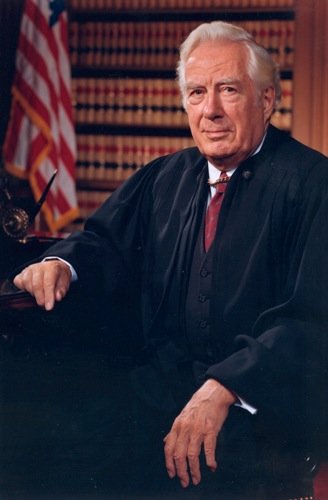

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Justice Lewis Powell found that the commission’s advertising prohibition, emphasizing the importance of protecting commercial speech under the First Amendment. Commercial speech, Powell wrote, “not only serves the economic interest of the speaker, but also assists consumers and furthers the societal interest in the fullest possible dissemination of information.” The Court has previously protected commercial speech, as Powell explained, “[i]n applying the First Amendment to this area, we have rejected the ‘highly paternalistic’ view that government has complete power to suppress or regulate commercial speech.” He cited the Court’s decision Virginia State Board of Pharmacy v. Virginia Citizens Consumers Council (1976) in which they established protections for commercial speech.

Powell then described the four-step analysis that the Court should employ when analyzing a prohibition of commercial speech. Commonly referred to as the Central Hudson Test, it includes the following questions:

Is the expression being targeted protected by the First Amendment?

Is the government’s interest substantial?

Does the regulation directly advance that government interest?

Is the regulation of speech more extensive than necessary to achieve the government’s interest?

If the prohibition on commercial speech passes the test, then it does not violate the First Amendment. In the case of Central Hudson, Powell found that the commission’s blanket ban on advertisements promoting the use of electricity failed the test because it was too broad and thus unconstitutional.

Concurring Opinion by Justice Stevens

In his concurring opinion, Justice John Paul Stevens wrote that while he agreed with the Court’s decision that the commission’s prohibition violated the First Amendment, he did not want to weigh in on whether or not the Central Hudson Test adequately protected commercial speech. Stevens also noted that one of the definitions of commercial speech used by the Court, which defined it as “expression related solely to the economic interests of the speaker and its audience,” was far too broad for him to agree with. Stevens concluded with a narrow view of commercial speech, explaining that while it is “afforded less constitutional protection than other forms of speech, [and] it is important that the commercial speech concept not be defined too broadly lest speech deserving of greater constitutional protection be inadvertently suppressed.”

Concurring Opinion by Justice Blackmun

Joined by Justice William Brennan, Justice Harry Blackmun wrote in his concurring opinion that while he agreed with the majority that the commission’s prohibition was too broad, he disagreed with their establishment of the Central Hudson Test as a rule of general applicability. He wrote that “the Court's four-part test is the proper one to be applied when a State seeks to suppress information about a product in order to manipulate a private economic decision that the State cannot or has not regulated or outlawed directly.” Blackmun, however, believed that applying this theory generally to commercial speech would be too restrictive.

Blackmun recognized the legitimate goal of promoting energy conservation on a local and national level, but found the prohibition on advertising to be too broad. Blackmun explained that “[p]ermissible restraints on commercial speech have been limited to measures designed to protect consumers from fraudulent, misleading, or coercive sales techniques. Those designed to deprive consumers of information about products or services that are legally offered for sale consistently have been invalidated.” He emphasized the idea that the government may only interfere in speech in the face of a clear and present danger, writing that absent such conditions, “government has no power to restrict expression because of the effect its message is likely to have on the public.”

Concurring Opinion by Justice Brennan

In his brief concurrence, Justice William Brennan noted that one of the challenges in this case was determining the specific intent and scope of the commission’s advertising policy. He wrote that “I find it impossible to determine on the present record whether the Commission's ban on all ‘promotional’ advertising, in contrast to ‘institutional and informational’ advertising is intended to encompass more than ‘commercial speech.’ I am inclined to think that Justice Stevens is correct that the Commission's order prohibits more than mere proposals to engage in certain kinds of commercial transactions.” Blackmun concluded that the commission’s policy was unconstitutional under the First Amendment and agreed with Justice Blackmun’s assertion that "[n]o differences between commercial speech and other protected speech justify suppression of commercial speech in order to influence public conduct through manipulation of the availability of information.”

Dissenting Opinion by Justice Rehnquist

In his solo dissent, Justice William Rehnquist disagreed with the Court’s assertion that commercial speech is entitled to the same level of protection under the First Amendment as all other forms of speech. Rehnquist voiced his concern that the Court’s decision to expand protections of commercial speech would return the Court to “the bygone era” of Lochner v. New York (1905), in which the Court employed a rational basis test for review and frequently struck down state economic regulations. Rehnquist explained that while he agrees with the standard set by the clear and present danger test for speech on public issues, the government should maintain the ability to regulate commercial speech.

Specifically, Rehnquist argued that since Central Hudson was a public utility, they were a state-created monopoly with different rights than privately-owned companies. Rehnquist explained the difference between a public utility and a private company when it comes to speech, writing that a public utility “fulfills a function that serves special public interests as a result of the natural monopoly of the service provided.” He then elaborated that “the extensive regulations governing decision-making by public utilities suggest that for purposes of First Amendment analysis, a utility is far closer to a state-controlled enterprise than is an ordinary corporation.” Rehnquist explained that this dynamic should grant the government broad discretion in determining what statements a public utility company can say.

![By Color negative by Robert S. Oakes - Library of Congress. [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=374955](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/65be8e7ea792fd0dd6c4ac2d/2354eed2-6452-4693-ac9c-42714c1c4beb/US_Supreme_Court_Justice_Lewis_Powell_-_1976_official_portrait.jpg)