Craig v. Boren

Case Overview

CITATION

ARGUED ON

DECIDED ON

DECIDED BY

429 U.S. 190

October 5, 1976

December 20, 1976

Legal Issue

Did Oklahoma’s law establishing different drinking ages for men and women violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment?

Holding

Yes, the law violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Plaintiffs of the landmark Supreme Court case Craig v. Boren together to celebrate its 40th anniversary at Oklahoma State University | Credit: Aubrie Bowlan/O'Colly

Background

In Oklahoma, a statute was enacted prohibiting the sale of “nonintoxicating” 3.2% beer to males under the age of 21 and to females under the age of 18. In response, Mark Walker, a 20 year old freshman at Oklahoma State University, and Carolyn Whitener, the owner of a convenience store and a licensed vendor in the state, brought a lawsuit against the statute in federal court. While the case proceeded through the court, Walker turned 21, so 18 year old Curtis Craig, also a student at Oklahoma State, joined the case as the third co-plaintiff.

The District Court judge dismissed their initial complaint, finding that the law was a reasonable exercise of the state’s power under the 21st Amendment. The decision was appealed and heard by a three-judge panel of the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals, who unanimously upheld the District Court’s ruling. After this setback, future Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg reached out to the plaintiffs’ lawyer on behalf of the ACLU to offer to file an amicus curiae in their favor. The lawyer accepted, and the case was granted certiorari by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Summary

7 - 2 decision for Craig

Craig

Boren

Brennan

Stewart

Marshall

Burger

Powell

Rehnquist

Stevens

Blackmun

White

Opinion of the Court

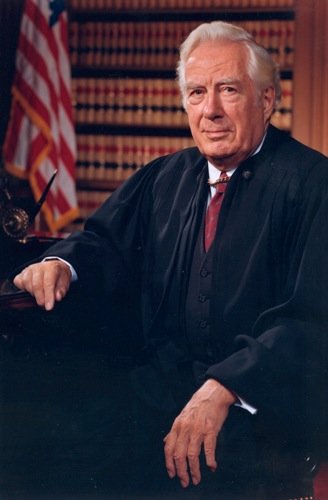

Writing for the Court, Justice William Brennan emphasized that gender-based classifications must meet a standard of heightened scrutiny. While the counsel for Oklahoma argued that the law aimed to enhance traffic safety by addressing statistical evidence suggesting that young males were more prone to driving under the influence of alcohol than females, Brennan found this evidence to be unpersuasive and insufficient to justify the gender-based distinction. He pointed out that the disparity in arrest rates for alcohol-related offenses between males and females in the 18-20 age group—while existent—was not substantial enough to warrant a categorical distinction based on sex. He noted that only 2% of males and 0.18% of females in the relevant age group had been arrested for driving under the influence, which he argued was an overly broad generalization and an inadequate basis for such a law. Brennan stated that “proving broad sociological propositions by statistics is a dubious business” and emphasized that the Equal Protection Clause does not allow for classifications based on loose-fitting generalities about gender behavior.

Brennan rejected Oklahoma’s argument that the statute could be justified under the Twenty-first Amendment, which grants states broad powers to regulate alcohol. He asserted that the Amendment does not permit states to impose invidious discrimination in violation of the Equal Protection Clause. In this case, Brennan found that the gender-based restriction on beer sales was not sufficiently connected to the state’s interest in traffic safety to survive constitutional scrutiny. Ultimately, Justice Brennan concluded that Oklahoma’s gender-based beer sales law was an invidious discrimination against males aged 18-20, in violation of the Equal Protection Clause. He found the law lacked the necessary substantial relation to the state’s goal of promoting traffic safety, reversing the lower court’s decision.

Concurring Opinion by Justice Powell

In his concurring opinion, Justice Lewis Powell explained that while he agrees with the Opinion of the Court, he had “reservations as to some of the discussion concerning the appropriate standard for equal protection analysis and the relevance of the statistical evidence.” Powell stated that while he agrees that the Court’s holding in Reed v. Reed (1971) is the most relevant precedent, he was concerned about the Court’s broad interpretation of it in this case. He explained, “Reed and subsequent cases involving gender-based classifications make clear that the Court subjects such classifications to a more critical examination than is normally applied when ‘fundamental’ constitutional rights and ‘suspect classes’ are not present.”

Powell also responded to Oklahoma’s statistical evidence, acknowledging that while they indicate that young men drive more and may be more inclined to drink, he was “not persuaded that these facts and the inferences fairly drawn from them justify this classification based on a three year age differential between the sexes, and especially one that is so easily circumvented as to be virtually meaningless.” He ultimately concluded that the gender based classification did not bear a “fair and substantial” relation to the state’s interest in traffic safety.