Duncan v. Louisiana

Case Overview

CITATION

391 U.S. 145 (1968)

ARGUED ON

January 17, 1968

DECIDED ON

December 21, 1968

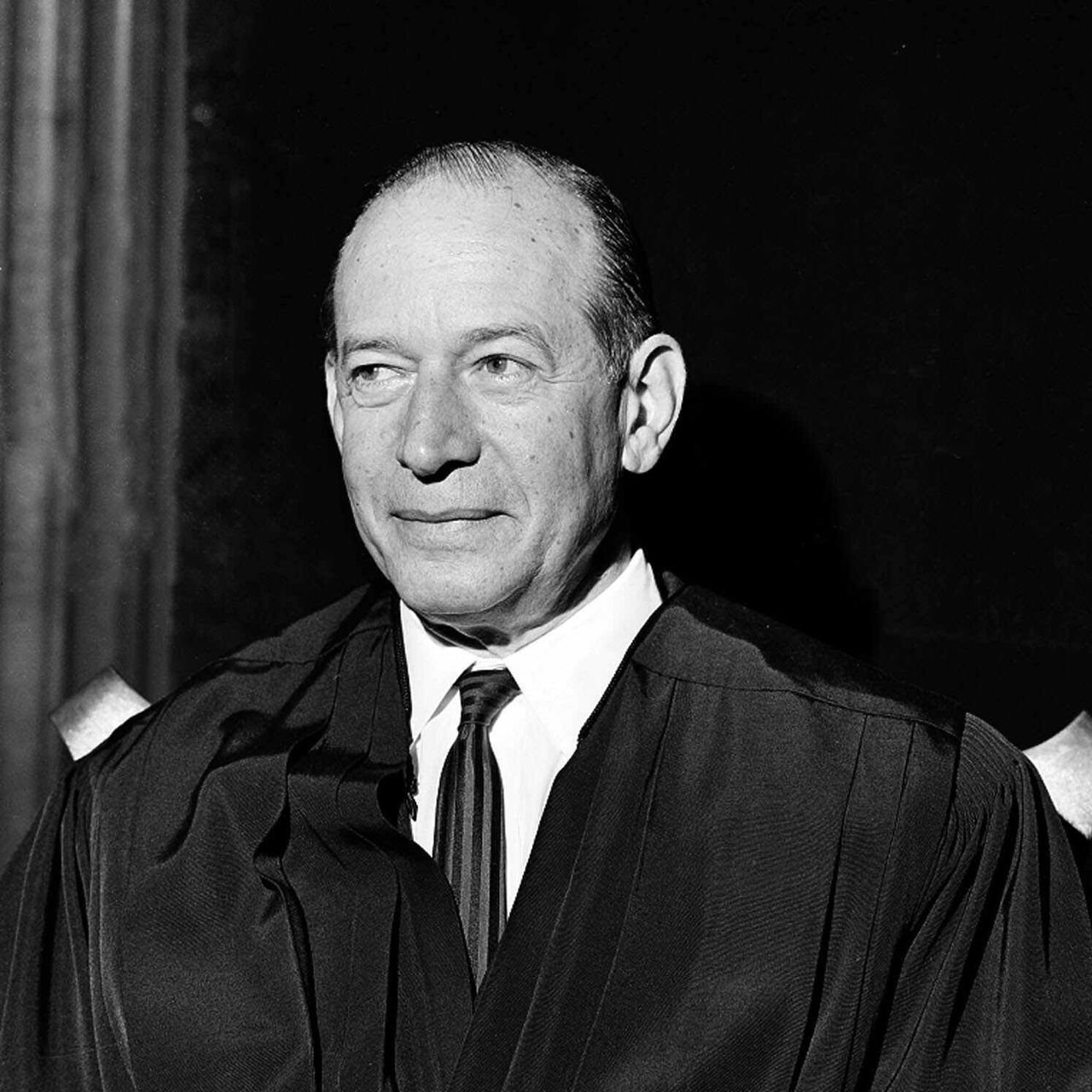

DECIDED BY

Legal Issue

Do the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments protect the right to a trial by jury in state prosecutions?

Holding

Yes, the Fourteenth Amendment protects the right to a trial by jury in all criminal cases that would come within the Sixth Amendment’s protection if they were tried in a federal court.

Gary Duncan in 1966 | Credit: AUGUSTA FILMS

Gary Duncan with Richard Sobol, the lawyer who argued his case before the Supreme Court (2020) | Credit: Anne Sobol via AP

Background

In October 1966, while driving in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana, 19-year-old Gary Duncan stopped his vehicle upon seeing his two younger cousins speaking with four white boys on the side of the road. Duncan was concerned for their safety, since racial tensions had increased due to recent incidents at a newly integrated school. The interaction, though contested in its specifics, resulted in an accusation that Duncan slapped one of the white boys on the elbow. Duncan and his cousins disputed the claim, describing the contact as a mere touch. He was ultimately charged with simple battery, which under state law was classified as a misdemeanor punishable by up to two years’ imprisonment and a $300 fine.

Despite his request for a jury trial, Duncan was denied this right based on the Louisiana Constitution, which only granted jury trials in cases where the punishment could involve capital punishment or imprisonment at hard labor. Duncan’s trial was held without a jury, and he was convicted and sentenced to 60 days in prison and fined $150.

Duncan appealed his conviction to the Louisiana Supreme Court, arguing that the denial of a jury trial violated his constitutional rights under the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments of the U.S. Constitution, but they denied his appeal. Duncan then petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court for certiorari, which they granted.

Summary

7 - 2 decision for Duncan

Duncan

Louisiana

Warren

Marshall

Douglas

Harlan II

Brennan

White

Stewart

Fortas

Black

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Justice Byron White held that the right to a jury trial is fundamental to the American justice system and is thus applicable to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment. White emphasized that the denial of a jury trial in serious criminal cases was inconsistent with both the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments.

White outlined the historical context and constitutional grounds for the Court’s decision, noting that the concept of a jury trial had been a long-standing fixture in English and American law that was widely regarded as a safeguard against tyranny and overreach by the government. He stressed that by the time the Constitution was adopted, the right to a jury trial was already entrenched as a critical component of liberty and justice. White argued that the Sixth Amendment’s guarantee of a jury trial in criminal proceedings extends to state courts via the Fourteenth Amendment, particularly in cases where serious offenses were charged, writing that “trial by jury in criminal cases is fundamental to the American scheme of justice,” and thus, states were compelled to provide jury trials in all criminal cases that would warrant such under federal law.

White also addressed the classification of crimes as petty or serious based on the penalties involved. He asserted that the authorized penalty for a crime significantly influenced its classification; serious crimes warranting more severe penalties should naturally require a jury trial. This was highlighted by Duncan’s circumstances, where the potential two-year imprisonment for simple battery qualified it as a serious crime deserving of a jury trial. White concluded, affirming the right to a trial by jury as a constitutional right essential to preserving the fundamental fairness and integrity of the criminal justice system.

Concurring Opinion by Justice Black

In his concurring opinion, Justice Hugo Black strongly supported the majority’s decision to extend the Sixth Amendment’s right to a jury trial to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment. He emphasized that the incorporation of the Bill of Rights was not only historically justified but also essential to ensuring fundamental liberties against state infringement.

Black began by reiterating his long-held view that the Fourteenth Amendment was intended to apply the first eight amendments of the Bill of Rights to the states. He criticized the selective incorporation doctrine, which only applied certain rights deemed “fundamental” to the states, advocating instead for the total incorporation of the Bill of Rights. He argued that the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment intended for its broad language to encompass all the guarantees of the Bill of Rights, stating “[m]y view has been and is that the Fourteenth Amendment, as a whole, makes the Bill of Rights applicable to the States.” Black cited historical evidence to support his view, asserting that both supporters and opponents of the Fourteenth Amendment understood it to mean the incorporation of the Bill of Rights. He cited speeches and writings from key figures involved in the amendment’s passage, such as Senator Jacob Howard, who explicitly mentioned the personal rights secured by the first eight amendments.

Black dismissed the argument that applying the Bill of Rights to the states would interfere with the autonomy of the states. He argued that protecting fundamental rights did not undermine federalism but rather ensured that states could not infringe upon essential liberties. He quoted Justice Goldberg’s concurring opinion in Pointer v. Texas (1965) in which he wrote, “to deny to the States the power to impair a fundamental constitutional right is not to increase federal power, but, rather, to limit the power of both federal and state governments in favor of safeguarding the fundamental rights and liberties of the individual.”

Dissenting Opinion by Justice Harlan II

In his dissenting opinion, Justice John Harlan II explained his disagreement with the majority’s decision to apply the right to a jury trial to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment and advocated for a more restrained approach to incorporating federal rights against the states. Harlan began by noting the ancient roots of the jury trial and its role in the American legal tradition, but he argued that the real question was whether the Constitution prohibited the State of Louisiana from trying charges of simple battery without a jury. In his view, the Constitution did not mandate this prohibition. He argued that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment required only fundamental fairness, not nationwide uniformity in criminal procedures, stating, “[t]he Due Process Clause does not command adherence to forms that happen to be old; and it does not impose on the States the rules that may be in force in the federal courts except where such rules are also found to be essential to basic fairness.”

Harlan criticized the majority for an approach that, in his opinion, was an uneasy compromise among various views on the Due Process Clause’s interpretation. He wrote, “[t]he Court has compromised on the ease of the incorporationist position, without its internal logic.” He emphasized that the Due Process Clause should be interpreted based on principles of fundamental fairness rather than automatically incorporating specific provisions of the Bill of Rights.

Harlan also highlighted the potential dangers of the incorporation approach, noting that it could lead to a uniformity that might water down important protections in an effort to impose federal standards on the states. He argued that this could undermine the diversity and flexibility that are key components of federalism. Harlan further pointed out that the historical and logical arguments against full incorporation were substantial, maintaining that due process was an evolving concept that should be defined by American traditions and the system of government. He advocated for a case-by-case determination of fairness, rather than a blanket application of federal standards to state procedures.