Gideon v. Wainwright

Case Overview

CITATION

372 U.S. 335 (1963)

ARGUED ON

January 15, 1963

DECIDED ON

March 18, 1963

DECIDED BY

OVERRULED

Betts v. Brady (1942)

Legal Issue

Does the Fourteenth Amendment protect the right to counsel for indigent defendants in charged with a felony in state courts?

Holding

Yes, the right of an indigent defendant to have the assistance of counsel is a fundamental right essential to a fair trial.

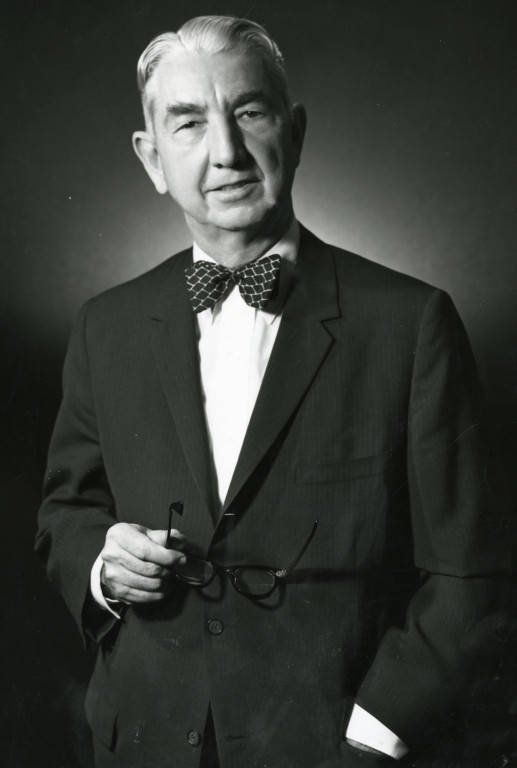

Mugshot of of Clarence Gideon taken at the Florida State Prison in Raiford, Florida (1961) | Credit: State Archives of Florida

Background

On June 3, 1961, Clarence Earl Gideon broke into the Harbor Poolroom in Panama City, Florida and stole money from the jukebox and cigarette machines. Gideon was caught and was charged with breaking and entering with intent to commit petty larceny.

During his first appearance in court, Gideon stated that he could not afford an attorney and requested that the court appoint one for him, but the presiding judge denied his request. The judge’s decision was based on Florida law that only allowed the appointment of counsel to indigent defendants in capital cases. Gideon represented himself at trial and was found guilty by the jury. He was subsequently sentenced to five years in prison.

Gideon appealed his conviction and filed a handwritten petition to the Florida Supreme Court, arguing that his conviction was unconstitutional because the trial court's refusal to appoint counsel violated his rights under the Constitution, but they denied his appeal. Gideon then petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court, and they granted certiorari.

Summary

9 - 0 decision for Gideon

Gideon

Wainwright

Warren

Clark

Douglas

Harlan II

Brennan

White

Stewart

Goldberg

Black

Opinion of the Court

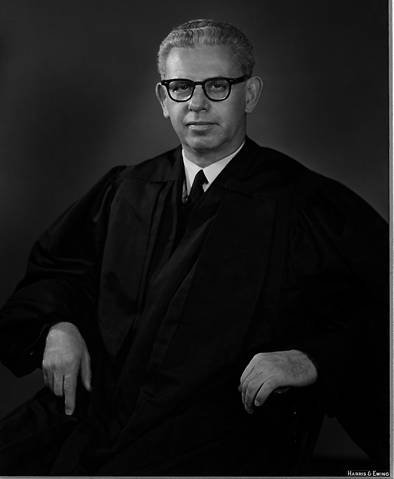

Writing for the Court, Justice Hugo Black held the right to counsel is a fundamental right that is essential for a fair trial and that it is applied to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause.

Black first noted the similarities between the circumstances of Gideon’s case and the defendant in Betts v. Brady (1942). In Betts, the Court held that the right to counsel had not been violated because the circumstances were “not so offensive to the common and fundamental ideas of fairness.” Black criticized Betts for its departure from precedent and asserted that it fails to recognize the essential role that legal representation plays in a fair trial. He pointed out that in Betts, the Court evaluated the need for counsel based on an “arbitrary determination” of trial complexity and the defendant’s ability to represent themselves, which he found to be a flawed approach. Black explained that by deciding that the appointment of counsel was not a fundamental right, “the Court […] made an abrupt break with its own well-considered precedents. In returning, to these old precedents, sounder we believe than the new, we but restore constitutional principles established to achieve a fair system of justice. Not only these precedents but also reason and reflection require us to recognize that in our adversary system of criminal justice, any person haled into court, who is too poor to hire a lawyer, cannot be assured a fair trial unless counsel is provided for him.

Black argued that the right to counsel in federal courts, unequivocally mandated by the Sixth Amendment, is equally essential in state courts to ensure justice and fairness. He emphasized that legal representation is necessary not just as a luxury but as vital for the protection of the accused’s rights. This is particularly important, he noted, given the complexity of criminal proceedings and the potential for severe consequences, including imprisonment. Black concluded that “[f]rom the very beginning, our state and national constitutions and laws have laid great emphasis on procedural and substantive safeguards designed to assure fair trials before impartial tribunals in which every defendant stands equal before the law. This noble ideal cannot be realized if the poor man charged with crime has to face his accusers without a lawyer to assist him.”

Concurring Opinion by Justice Douglas

While he agreed with the Opinion of the Court, Justice Owen Douglas explained that he wrote separately because “a brief historical resume of the relation between the Bill of Rights and the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment seems pertinent.”

Douglas pointed out that a majority of the Court has never settled on a single interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment. He noted that while some Justices view the rights protected under the Fourteenth Amendment as less than those protected by the Bill of Rights, “that view has not prevailed and rights protected against state invasion by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment are not watered-down versions of what the Bill of Rights guarantees.”

Douglas concluded, “[y]et, happily, all constitutional questions are always open. […] And what we do today does not foreclose the matter.”

Concurring Opinion by Justice Clark

In his brief opinion, Justice Tom Clark concurred with the Court’s decision to overrule Betts v. Brady, writing that “[i]t is equally clear from the above cases, all decided after Betts v. Brady, that the Fourteenth Amendment requires such appointment in all prosecutions for capital crimes.”

While he concurred in the reversal of Betts, Clark argued that the right counsel in capital cases should apply to noncapital cases to maintain fairness and consistency in the legal process. He criticized the distinction between capital and noncapital cases as lacking a logical foundation, pointing out that the quality of justice should not vary based on the severity of the potential penalty. He wrote, “[h]ow can the Fourteenth Amendment tolerate a procedure which it condemns in capital cases on the ground that deprival of liberty may be less onerous than deprival of life—a value judgment not universally accepted—or that only the latter deprival is irrevocable?”

Concurring Opinion by Justice Harlan

In his concurring opinion, Justice John Harlan II supported the majority’s decision to overrule Betts v. Brady but advocated for a more respectful acknowledgment of its historical context and judicial reasoning. Harlan argued that the precedent set by Betts was not an “abrupt break” with earlier decisions but rather a continuation of a cautious approach to extending federal constitutional protections to state actions. He noted, “It is evident that these limiting facts were not added to the opinion as an afterthought; they were repeatedly emphasized […] and were clearly regarded as important to the result.” Harlan criticized the majority for not giving due credit to the case and suggested that the Betts decision was an extension rather than a contradiction of precedent, providing states with the flexibility to adapt the right to counsel based on local needs and conditions.

Harlan agreed with the majority that it was time to formally abandon the “special circumstances” rule of Betts in noncapital cases, writing “[t]he time has now come when it should be similarly abandoned in noncapital cases, at least as to offenses which, as the one involved here, carry the possibility of a substantial prison sentence.” Harlan emphasized that while he agrees with the need to guarantee counsel in all criminal prosecutions as a fundamental right, this should not imply an automatic adoption of all aspects of federal procedural rights in state systems. He argued for a balanced approach that considers the unique contexts of state legal systems while adhering to constitutional principles, asserting, “When we hold a right or immunity, valid against the Federal Government, to be ‘implicit in the concept of ordered liberty,’ and thus valid against the States, I do not read our past decisions to suggest that by so holding, we automatically carry over an entire body of federal law and apply it in full sweep to the States.”