Gitlow v. New York

Case Overview

CITATION

536 U.S. 304 (2002)

ARGUED ON

REARGUED ON

DECIDED ON

DECIDED BY

April 12, 1923

November 23, 1923

June 8, 1925

Legal Issues

Do the freedoms of speech and press under the First Amendment of the Constitution apply to the states?

Does New York’s Criminal Anarchy Law violate the First Amendment?

Holding

Yes, but states can enforce statutes that restrict the rights to speech and press in the interest of national security.

No, and Gitlow’s advocacy was not protected by the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment.

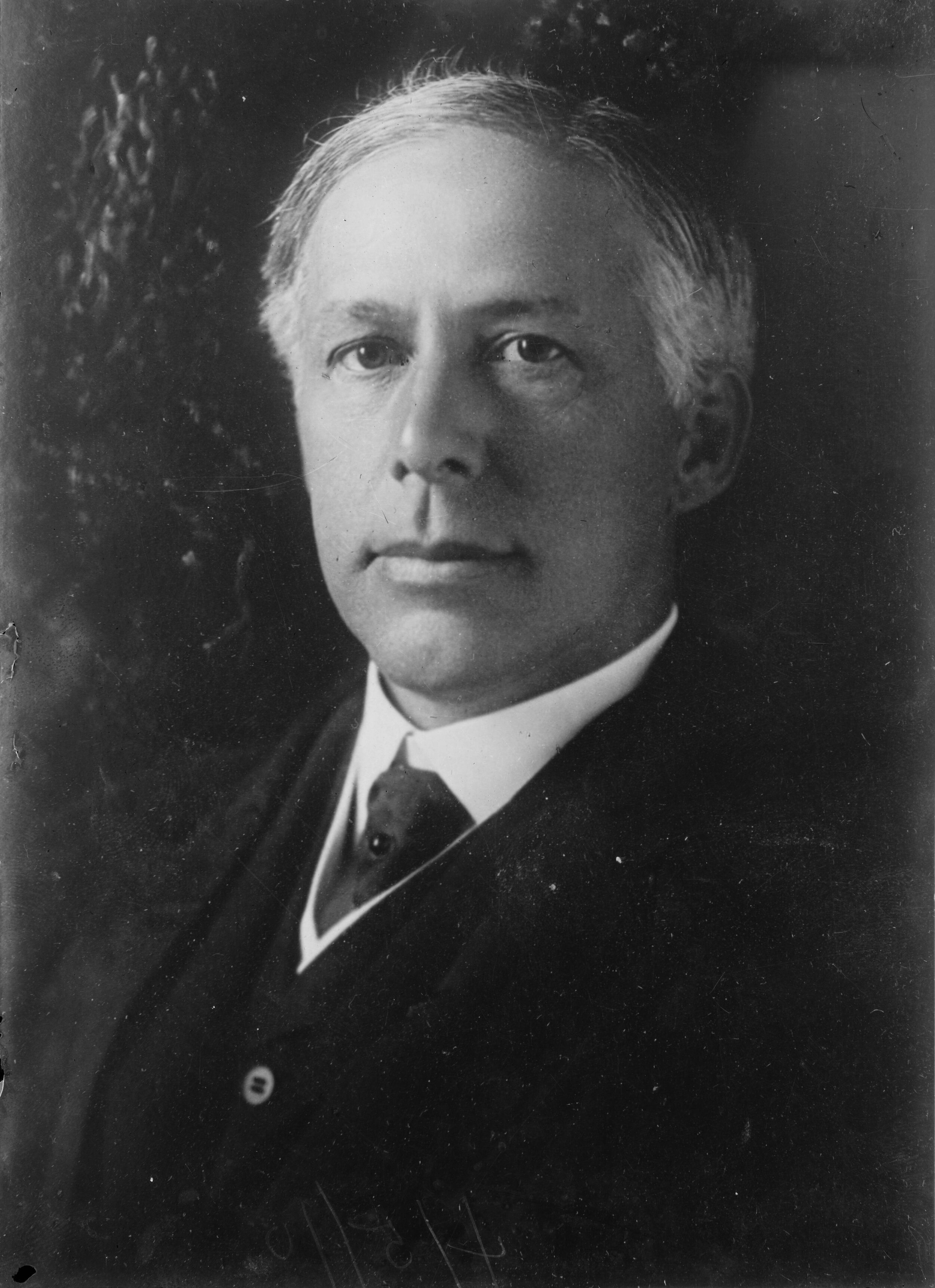

Benjamin Gitlow’s mugshot

Background

In response to President McKinley's assassination by an anarchist in 1901, New York passed the 1902 Criminal Anarchy Law. This law aimed to prevent the rise of American Bolsheviks by targeting activists advocating for the overthrow of the government through violent revolutionary means. During the Red Scare of 1919–20, leftists, including anarchists, Bolshevik sympathizers, labor activists, and members of communist or socialist parties, faced convictions under the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 for their socialist activism.

In 1920, Benjamin Gitlow, a Socialist Party member and former New York State Assemblyman, was charged with criminal anarchy for publishing a document titled "Left Wing Manifesto" in The Revolutionary Age newspaper. His defense argued that the manifesto was a historical analysis rather than advocacy and that it did not incite any specific or material actions against the government, but Gitlow was ultimately convicted and sentenced to 5 to 10 years in prison. After serving more than two years, Gitlow's motion to appeal was granted, and he was released on bail. Both the appellate court and the New York Court of Appeals, the state’s highest court, upheld his conviction.

Summary

9 — 0 decision for New York

Gitlow

Issue 1

New York

Taft

White

Holmes

Sutherland

Sutherland

Brandeis

Issue 2

7 — 2 decision for New York

Gitlow

New York

Holmes

Brandeis

Van Devanter

Van Devanter

Stone

Stone

McReynolds

McReynolds

Sanford

Sanford

Butler

Butler

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Justice Sutherland acknowledged the importance of safeguarding free speech, noting that the freedoms of speech and press are “fundamental personal rights and liberties” protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, thereby applying them to the states under the incorporation doctrine.

While Sutherland defended the protection of the right to free speech, he also recognized that the right is not absolute. He cited previous Supreme Court decisions, such as Schenck v. United States, which established the "clear and present danger" test for determining when speech can be restricted. According to this test, speech that presents a clear and present danger of inciting unlawful action can be subject to regulation.

Building on this framework, Sutherland analyzed the statute at issue in Gitlow v. New York, which prohibited advocating for the violent overthrow of the government. He argued that such advocacy posed a direct threat to the stability of the government and the safety of its citizens. Sutherland wrote, "Every idea is an incitement. It offers itself for belief and if believed, it is acted on unless some other belief outweighs it or some failure of energy stifles the movement at its birth." Here, he emphasized the potential for ideas to inspire action, highlighting the need for caution when considering speech that advocates for violent revolution.

Sutherland also emphasized that the state has a legitimate interest in preserving order and preventing the disruption of society. He wrote, “The greater the importance of safeguarding the community from incitements to the overthrow of our institutions by force and violence, the more imperative is the need to preserve inviolate the constitutional rights of free speech, free press, and free assembly.” Sutherland is essentially describing the balancing act that exists between protecting free speech and maintaining social stability. Sutherland ultimately concluded by upholding the constitutionality of the New York statute, finding that it served a legitimate government interest in keeping peace.

Dissenting Opinion by Justice Holmes

In his dissenting opinion, Justice Holmes articulated a view that emphasized the importance of protecting even radical speech, unless it presents a clear and present danger of imminent harm. His dissent affirmed the principles of free expression and emphasized the critical importance of allowing even unpopular or controversial speech to circulate freely so long as it does not pose an immediate threat to public safety or the functioning of the government.

Holmes criticized the majority's application of the "clear and present danger" test, arguing that it was too broad and could potentially stifle legitimate political dissent. He wrote, “Every idea is an incitement. It offers itself for belief and if believed it is acted on unless some other belief outweighs it or some failure of energy stifles the movement at its birth. The only difference between the expression of an opinion and an incitement in the narrower sense is the speaker's enthusiasm for the result. Eloquence may set fire to reason.” Holmes believed that the mere advocacy of ideas, without a direct incitement to violence or illegal action, should be protected under the First Amendment.

Holmes also cautioned against the government's use of censorship to suppress dissenting voices, warning of the dangers of authoritarianism. He argued that allowing the state to silence certain viewpoints could set a dangerous precedent and undermine the principles of democracy. Holmes famously wrote, “Persecution for the expression of opinions seems to me perfectly logical. If you have no doubt of your premises or your power, and want a certain result with all your heart, you naturally express your wishes in law, and sweep away all opposition.” Holmes's dissent championed a robust interpretation of free speech rights, advocating for the protection of even radical or unpopular ideas unless they present an immediate and tangible threat to public safety or governmental functions.

“I think that we should be eternally vigilant against attempts to check the expression of opinions that we loathe and believe to be fraught with death, unless they so imminently threaten immediate interference with the lawful and pressing purposes of the law that an immediate check is required to save the country.”

— Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes