Hodges v. United States

Case Overview

CITATION

ARGUED ON

DECIDED ON

OVERRULED BY

203 U.S. 1 (1906)

April 23, 1906

May 28, 1906

DECIDED BY

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co. (1968)

Legal Issue

Does the Thirteenth Amendment give Congress the authority to intervene against racially-motivated interference with labor contracts?

Holding

No, the Thirteenth Amendment does not authorize Congress to intervene against racially-motivated interference with labor contracts.

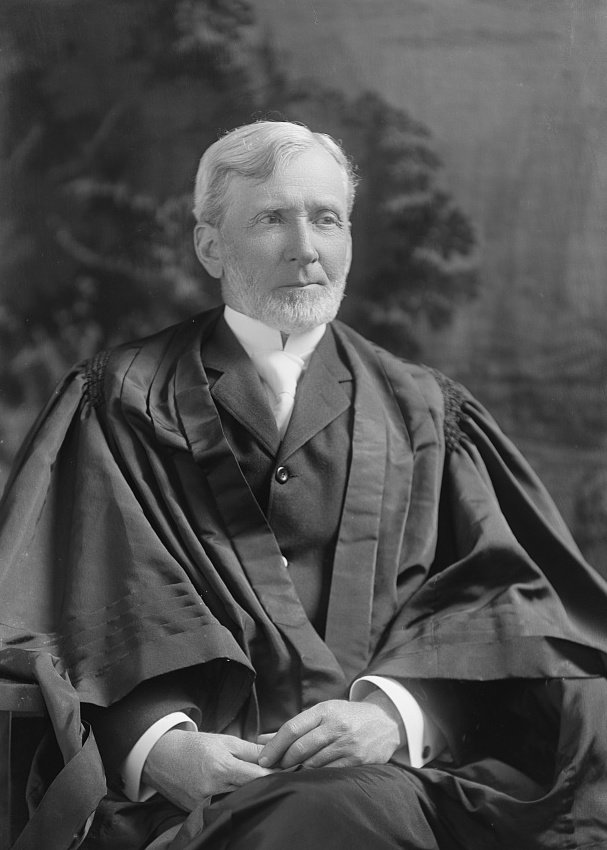

U.S. Attorney General Philander C. Knox, who approved the DOJ investigation into “white-capping” | Credit: Library of Congress

Background

In 1903, the U.S. Attorney General Philander C. Knox approved an investigation into a group of white men in Arkansas for conspiring to prevent Black workers from holding jobs at a sawmill. These men intimidated and threatened the workers, attempting to force them to abandon their employment. The workers had contracts with the sawmill, and the defendants’ actions were charged under federal civil rights statutes, specifically sections 1977 and 5508 of the Revised Statutes, which aimed to protect the rights of citizens to make and enforce contracts. In October 1903, the men were indicted by a federal grand jury.

The central issue was whether the Thirteenth Amendment granted the federal government the authority to prosecute individuals for interfering with the labor contracts of Black citizens. The prosecution argued that the defendants’ actions violated the workers’ rights guaranteed by the Thirteenth Amendment, which was intended to abolish slavery and involuntary servitude and protect the newly freed individuals’ right to freely engage in labor contracts.

Summary

7 - 2 decision for Hodges

Hodges

United States

McKenna

Brown

Peckham

Fuller

Day

Holmes

Brewer

Harlan

White

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Justice David Brewer argued that before the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, the national government had no jurisdiction over individual wrongs like the one charged in this indictment. Reaffirming the principle that the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments were restrictions upon state action, not actions by private individuals, Brewer focused on whether the Thirteenth Amendment provided Congress with the power to legislate against individual actions that interfered with the rights of others based solely on race. Brewer referred to the Slaughter-House Cases, emphasizing that the privileges and immunities of citizens were primarily governed by state laws, not federal. He argued that although the Thirteenth Amendment did abolish slavery and involuntary servitude, it did not extend federal power to protect against every wrong committed by private individuals. The Amendment prohibited the specific condition of slavery or involuntary servitude, but Brewer insisted that it did not intend to cover all forms of discrimination or personal wrongs.

Brewer discussed the Tenth Amendment, emphasizing that the national government is one of enumerated powers and that the powers not delegated to the United States are reserved to the states or the people. He believed that the Thirteenth Amendment did grant Congress some additional powers but maintained that any legislation directed against individual action not previously warranted must find its authority directly in the amendment. According to Brewer, protecting individuals from interference by other individuals was within the states’ jurisdiction, not the federal government’s.

Additionally, Brewer pointed out that the Thirteenth Amendment was intended to address the specific conditions of slavery and involuntary servitude, a state of compulsory service to another. Brewer argued that not every wrong that could infringe on an individual's rights amounted to imposing slavery. He expressed that acts of personal assault, trespass, or intimidation, while wrongful, did not reduce an individual to a condition of slavery. Hence, Congress's authority under the Thirteenth Amendment did not extend to every form of private discrimination or personal wrong. Brewer ultimately concluded that the federal government did not have jurisdiction in this case because the Thirteenth Amendment did not grant it the power to legislate against private acts of discrimination. He emphasized that the amendment was specifically focused on ending the condition of slavery and involuntary servitude, not regulating every individual wrong, leaving the responsibility to address such private actions with state governments, not the federal judiciary.