In Re Winship

Case Overview

CITATION

397 U.S. 358 (1970)

ARGUED ON

January 20, 1970

DECIDED ON

March 31, 1970

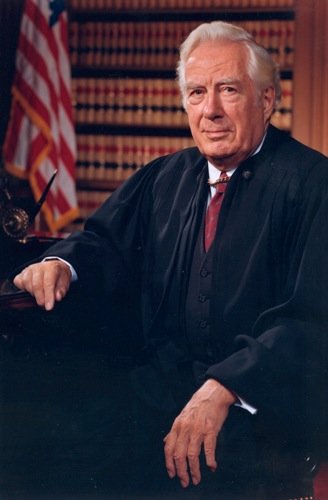

DECIDED BY

Legal Issue

Does the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment require that juvenile defendants be found guilty “beyond a reasonable doubt” in criminal prosecutions?

Holding

Yes, the Fourteenth Amendment requires that juvenile defendants be found guilty “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Herbert Niccolls, a juvenile sentenced to life in prison, pictured at the Walla Walla State Penitentiary in Idaho (1931) | Credit: WSP photo via WSU

Background

In New York, twelve-year-old Samuel Winship was charged under the state’s Juvenile Delinquent Act. The charge against Winship stemmed from an accusation that he had stolen $112 from a woman's purse at a supermarket, which was classified as larceny. If committed by an adult, the offense required proof “beyond a reasonable doubt” for conviction, but in juvenile proceedings, the state only needed to establish guilt by a “preponderance of the evidence,” a standard used typically in civil cases.

After a hearing in the Family Court of New York, Winship was found guilty of the charge based on the lower standard of proof. The court concluded that it was more likely than not that Winship had committed the theft, and as a result, he was adjudged a juvenile delinquent. Winship was placed in a state school for an initial period of 18 months, subject to annual extensions until his 18th birthday.

Winship appealed the decision, arguing that the use of a lower standard of proof violated his due process rights under the Fourteenth Amendment. The Appellate Division of the New York Supreme Court affirmed the lower court's decision, and the New York Court of Appeals denied further review. Winship's case was then brought before the Supreme Court, and they granted certiorari.

Summary

5 - 3 decision for Winship

Winship

Dissent

Burger

Douglas

Harlan II

Brennan

White

Stewart

Marshall

Black

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Justice William Brennan held that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment requires that determinations of guilt must be made with “proof beyond a reasonable doubt” in all criminal prosecutions, including those with juvenile defendants.

Brennan argued that the reasonable doubt standard plays a crucial role in reducing the risk of wrongful convictions and explained that such a standard provides concrete substance to the presumption of innocence, a fundamental principle in the administration of criminal justice. Brennan quoted the Court's ruling in Speiser v. Randall (1958), which stated, “[t]here is always in litigation a margin of error, representing error in factfinding, which both parties must take into account. Where one party has at stake an interest of transcending value—as a criminal defendant his liberty—this margin of error is reduced as to him by the process of placing on the other party the burden of . . . persuading the factfinder at the conclusion of the trial of his guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Additionally, Brennan emphasized the societal importance of the reasonable doubt standard, stating that it commands respect and confidence in the criminal justice system. He wrote, “use of the reasonable doubt standard is indispensable to command the respect and confidence of the community in applications of the criminal law. It is critical that the moral force of the criminal law not be diluted by a standard of proof that leaves people in doubt whether innocent men are being condemned.” Brennan concluded that the safeguard of proof beyond a reasonable doubt is as much required as other trial rights protected by the Constitution.

Concurring Opinion by Justice Harlan II

In his concurring opinion, Justice Harlan II emphasized his agreement with the majority that the standard of “proof beyond a reasonable doubt” is constitutionally required in juvenile delinquency proceedings, but he provided additional reasoning to highlight the broader implications and necessity of this standard.

Harlan posited that in any judicial proceeding involving disputed facts, a factfinder cannot achieve unassailable accuracy but can only form a belief about what probably happened and explained that a standard of proof instructs the factfinder on the degree of confidence society expects in the correctness of factual conclusions. He further noted that the factfinder’s conclusions could be wrong despite best efforts, and the standard of proof influences the relative frequency of two types of errors: convicting an innocent person or acquitting a guilty one. The standard of proof reflects an assessment of the comparative social costs of these erroneous outcomes.

In Harlan’s view, the reason for different standards of proof in civil and criminal cases is clear. In civil cases, society views erroneous judgments in favor of either party as equally serious, justifying the preponderance of the evidence standard. In criminal cases, however, society views the conviction of an innocent person as far more severe than the acquittal of a guilty one. This difference justifies the higher standard of proof beyond a reasonable doubt in criminal cases to minimize the risk of wrongful convictions. Harlan emphasized that this reasoning applies equally to juvenile delinquency proceedings, where the consequences of an erroneous factual determination include the loss of personal liberty and potential stigma for the youth involved. He asserted that subjecting a juvenile to the possibility of institutional confinement on less evidence than required to convict an adult is fundamentally unfair and concluded, “[a]lthough there are no doubt costs to society (and possibly even to the youth himself) in letting a guilty youth go free, I think here, as in a criminal case, it is far worse to declare an innocent youth a delinquent. I therefore agree that a juvenile court judge should be no less convinced of the factual conclusion that the accused committed the criminal act with which he is charged than would be required in a criminal trial.”

Dissenting Opinion by Chief Justice Burger

In his brief dissent, Chief Justice Warren Burger argued that the juvenile justice system was never meant to mirror the criminal justice system established for adults. He explained, “[t]he original concept of the juvenile court system was to provide a benevolent and less formal means than criminal courts could provide for dealing with the special and often sensitive problems of youthful offenders. Since I see no constitutional requirement of due process sufficient to overcome the legislative judgment of the States in this area, I dissent from further strait-jacketing of an already overly restricted system. What the juvenile court system needs is not more but less of the trappings of legal procedure and judicial formalism; the juvenile court system requires breathing room and flexibility in order to survive, if it can survive the repeated assaults from this Court.”

Dissenting Opinion by Justice Black

In his dissenting opinion, Justice Hugo Black argued for a strict interpretation of the Constitution and cautioned against judicial overreach. Black disagreed with the ruling that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment requires proof beyond a reasonable doubt in juvenile delinquency proceedings.

Black began by questioning the majority’s reliance on precedent, noting that the Court had never clearly held that proof beyond a reasonable doubt is either expressly or impliedly commanded by any provision of the Constitution. He emphasized the importance of adhering to the explicit text of the Constitution and pointed out that it does not mention the standard of proof for criminal convictions. Black noted that the Constitution provides specific procedural protections, such as the right to counsel, indictment, and trial by jury, but it does not specify proof beyond a reasonable doubt. He stated, “[t]he Constitution thus goes into some detail to spell out what kind of trial a defendant charged with crime should have, and I believe the Court has no power to add to or subtract from the procedures set forth by the Founders.”

Black expressed concern about the Court's tendency to impose its own standards of fairness rather than adhering strictly to the Constitution's text. He argued that the majority's decision was based on a subjective interpretation of “fair treatment,” which he believed was not grounded in the Constitution. He warned against this approach, stating, “[a]s I have said time and time again, I prefer to put my faith in the words of the written Constitution itself rather than to rely on the shifting, day-to-day standards of fairness of individual judges”

Additionally, Black discussed the historical context of due process, explaining that it originally meant proceedings according to the “law of the land” as it existed at the time. He emphasized that this phrase was intended to protect against arbitrary actions by the government, not to grant the judiciary the power to define what is fundamentally fair. He opined, “[o]ur ancestors' ancestors had known the tyranny of the kings and the rule of man and it was, in my view, in order to insure against such actions that the Founders wrote into our own Magna Carta the fundamental principle of the rule of law, as expressed in the historically meaningful phrase ‘due process of law.’”