New York Times Co. v. Sullivan

Case Overview

CITATION

376 U.S. 254 (1964)

ARGUED ON

January 6, 1964

DECIDED ON

March 9, 1964

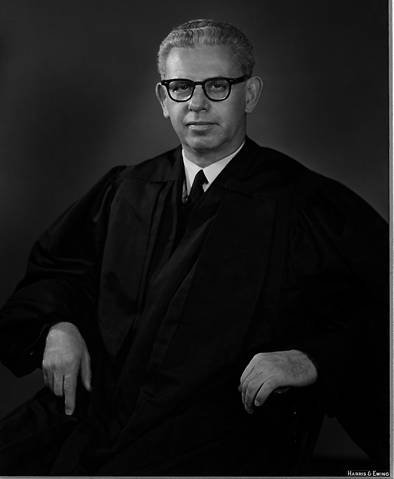

DECIDED BY

Legal Issue

Does a public official have to show that defamatory statements were made with actual malice to be able to sue a media publication for damages?

Holding

Yes, a public official must show that the statements were made with actual malice to sue for damages.

Advertisement published by the NYT seeking donations for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Background

On March 29, 1960, the New York Times published an advertisement titled “Heed Their Rising Voices,” which advocated for donations to defend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on perjury charges. The advertisement included three factually inaccurate statements that the Montgomery Public Safety Commissioner, L.B. Sullivan, took issue with. First, the advertisement claimed that the police had “ringed” the campus, which exaggerated presence. Second, the article falsely claimed that the dining hall had been padlocked “in an attempt to starve them into submission,” but the dining hall had never padlocked. Lastly, the advertisement reported that Dr. King had been arrested seven times, but the accurate number was four.

Sullivan filed a libel action against the New York Times under Alabama law, which classified a publication as ‘libelous per se’ if the words have a tendency to injure a person’s reputation or bring them into public contempt. Once these conditions were met, Alabama law dictated that the only defense against a charge of libel is to persuade the jury that their work was true. Once that had been established, the defendant had no defense outside of trying to persuade the jury that they were completely truthful. A jury in state court ultimately awarded Sullivan $500,000 in damages and the State Supreme Court affirmed the judgement before it was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Summary

Unanimous decision for the New York Times

New York Times

Sullivan

Warren

Harlan

Black

Douglas

Stewart

Brennan

Clark

Goldberg

White

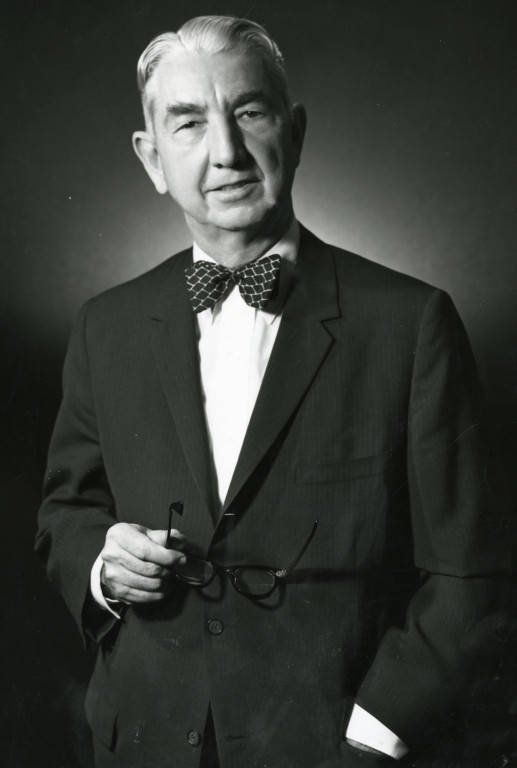

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Justice William Brennan Jr. held that in order for a statement against a public official to be deemed defamatory, it must be proved that the statement was made with “actual malice.” Brennan argued that inherent in the right to free speech is protection from the criticism of government, and that this is especially true as applied to the press. He quoted President Madison, who said that “some degree of abuse is inseparable from the proper use of every thing; and in no instance is this more true than in that of the press.” The importance of the First Amendment, Brennan argues, is that it offers a robust protection of the rights to free speech and a free press.

Under common law, a statement is defamatory simply if it’s false and damages an individual’s reputation. Brennan warned that using the common law standard for defamation would have a chilling effect on speech critical of the government, writing that it “dampens the vigor and limits the variety of public debate” and that it’s “inconsistent with the First and Fourteenth Amendments.” Brennan feared that using this standard would lead to self-censorship over fears that they might face a libel lawsuit and be forced to pay expensive judgements.

In the case at hand, Brennan wrote that “[t]he present advertisement, as an expression of grievance and protest on one of the major public issues of our time, would seem clearly to qualify for the constitutional protection. The question is whether it forfeits that protection by the falsity of some of its factual statements and by its alleged defamation of respondent.” In response to that question, Brennan wrote that an “erroneous statement is inevitable in free debate, and. . . must be protected if the freedoms of expression are to have the breathing space that they need. . . to survive.” Brennan concluded that a statement can only be considered defamatory is it is made with the knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard as to its legitimacy. Ultimately, Brennan wrote that the First Amendment reflects “a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open.”