North Carolina v. Alford

Case Overview

CITATION

400 US 25 (1970)

ARGUED ON

November 17, 1969

DECIDED ON

November 23, 1970

DECIDED BY

REARGUED ON

October 17, 1970

Legal Issue

Does the Constitution prevent a judge from accepting a guilty plea from a defendant who wants to plead guilty while maintaining their innocence under extreme duress?

Holding

No, there are no constitutional barriers that prevent a judge from accepting a guilty plea from a defendant who wants to plead guilty while maintaining their innocence under extreme duress

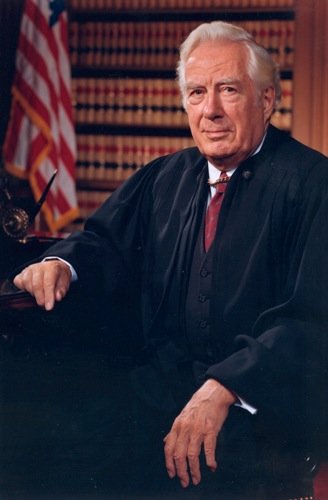

Robert Morgan, the Attorney General of North Carolina, argued the case on behalf of the appellant | Credit: William E. Sauro/The New York Times

Background

On November 22, 1963, Henry Alford and rented a room at a “party house” in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and allegedly got into a fight with its owner, Nathaniel Young. Later that evening, Young was murdered Young with a shotgun, and in December, Alford was indicted for first-degree murder. Facing the possibility of the death penalty if convicted at trial, Alford entered a plea of guilty to second-degree murder, despite maintaining his innocence.

Alford’s case initially went through the North Carolina state courts, where his guilty plea was accepted, and he was sentenced to a 30-year prison term. However, Alford later sought to withdraw his plea, contending that it was made under the duress of the potential death penalty and was therefore not made voluntarily. His request was denied, and the decision was upheld by the North Carolina Supreme Court, which ruled that a voluntary plea includes those entered to avoid a potentially harsher sentence. The Supreme Court then granted certiorari.

Summary

6 - 3 decision for North Carolina

North Carolina

Alford

Black

Douglas

Marshall

Harlan II

Stewart

Brennan

Burger

White

Blackmun

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the majority, Justice Byron White held that a guilty plea is constitutionally valid if it represents a voluntary and intelligent choice among the available options to the defendant, even if they professe their innocence. White began by affirming the principle that a plea of guilty must be a voluntary and intelligent choice among the alternatives available to the defendant. He referenced the Court’s decision in Brady v. United States (1970), which held that a guilty plea is not compelled within the meaning of the Fifth Amendment if it is entered to avoid the possibility of the death penalty. He emphasized, however, that the validity of a guilty plea does not depend on the defendant’s actual guilt but rather on whether the plea was made voluntarily and with an understanding of its consequences. White acknowledged that while most guilty pleas involve an admission of guilt, the Constitution does not require such an admission for the plea to be valid. He stated, “[a]n individual accused of crime may voluntarily, knowingly, and understandingly consent to the imposition of a prison sentence even if he is unwilling or unable to admit his participation in the acts constituting the crime.”

White then addressed the specific circumstances of Alford’s case. He noted that the trial court had conducted a thorough examination before accepting the plea, including hearing testimony that provided a strong factual basis for the charge. Alford's decision to plead guilty was made with the advice of competent counsel and was motivated by a desire to avoid the death penalty and limit his exposure to a 30-year sentence, so White concluded that the trial judge did not commit a constitutional error in accepting Alford’s guilty plea, despite Alford’s protestations of innocence.

Dissenting Opinion by Justice Brennan

In his dissenting opinion, Justice William Brennan argued that accepting a guilty plea despite the defendant’s protested innocence undermines the integrity of the judicial system and fails to ensure the voluntariness and intelligence required for a valid guilty plea. Brennan began by referencing his dissent in Brady v. United States (1970), where he contended that a guilty plea induced by the threat of the death penalty could not be considered voluntary. He reiterated his belief that any influence from outside influences must be weighed when accepting a plea, stating, “I adhere to the view that, in any given case, the influence of such an unconstitutional threat ‘must necessarily be given weight in determining the voluntariness of a plea.’”

Brennan also highlighted the problematic nature of allowing guilty pleas from defendants who maintain their innocence, as they contradict the very basis of admitting guilt. He stated, “I believe that at the very least such a denial of guilt is also a relevant factor in determining whether the plea was voluntarily and intelligently made.” He expressed concern that the acceptance of guilty pleas under these circumstances could lead to wrongful convictions and argued that the judicial system should not permit convictions based on pleas entered under duress or fear of harsher penalties. Ultimately, Brennan concluded that Alford’s plea was not voluntary because it was driven by fear of the death penalty. He argued that the facts demonstrated Alford was “so gripped by fear of the death penalty” that his decision to plead guilty was “the product of duress as much so as choice reflecting physical constraint.”