Ohio v. Roberts

Case Overview

CITATION

448 U.S. 56 (1980)

ARGUED ON

November 26, 1979

DECIDED ON

June 25, 1980

DECIDED BY

OVERRULED BY

Crawford v. Washington (2002)

Legal Issue

Does the introduction of prior witness testimony who had not been cross-examined violate the Confrontation Clause of the Sixth Amendment?

Holding

No, out-of-court statements can be admissible if they bear an adequate “indicia of reliability” and if a good-faith effort has been made to secure the witness.

The county courthouse in Lake County, Ohio, where the charges against Roberts originated | Credit: Lake County Court of Common Pleas

Background

On January 7, 1975, Herschel Roberts was arrested in Lake County, Ohio on charges of forgery of a check and possession of stolen credit cards of Amy and Bernard Isaacs. At the preliminary hearing, several witnesses were called and testified under oath, including Bernard Isaacs and his daughter, Anita. Shortly after, a county grand jury indicted Roberts on charges of forgery, receiving stolen property, and possession of heroin.

At trial, the admissibility of Anita Isaacs’ testimony was brought into question. Isaacs was unavailable to testify in person due to her relocation to another state and the prosecution’s inability to contact her. As a result, the prosecution sought to introduce her previous testimony from the preliminary hearing. While Roberts did have the opportunity to cross-examine Isaacs at the preliminary hearing, the question still arose as to whether or not that testimony could be admitted at trial.

Roberts was ultimately convicted, and he appealed his conviction on the grounds that admitting the absent witness’ prior testimony violated his Sixth Amendment right to confront witnesses against him as incorporated against the states through the Fourteenth Amendment. The Ohio Court of Appeals reversed his conviction, concluding that the prosecution failed to show a “good-faith” effort to secure the absent witness’ presence at trial. The case was appealed to the Ohio Supreme Court, which reversed the lower court’s decision.

Summary

6 - 3 decision for Ohio

Ohio

Roberts

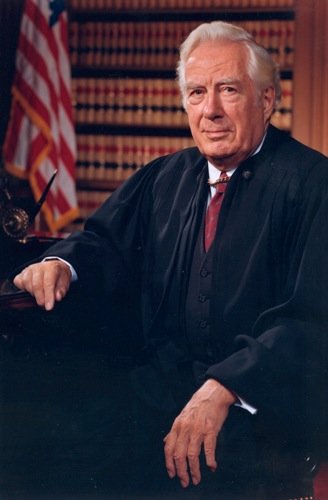

Burger

Stevens

Blackmun

Brennan

White

Stewart

Marshall

Powell

Rehnquist

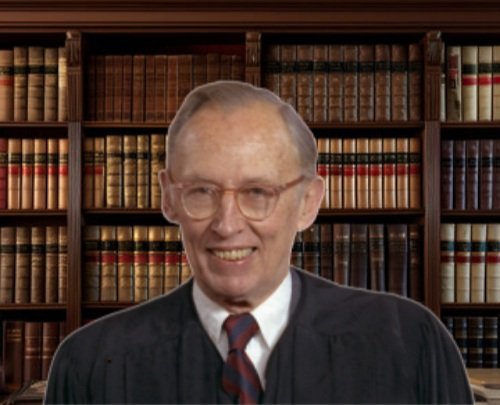

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Justice Harry Blackmun explained that the Confrontation Clause of the Sixth Amendment generally requires that a witness be present at trial to allow for cross-examination, but acknowledged exceptions when the witness is unavailable and the testimony bears adequate “indicia of reliability.” He outlined that when a hearsay declarant is not present for cross-examination at trial, the prosecution must show that the witness is unavailable despite good-faith efforts to secure their presence. Additionally, the testimony must be reliable, which can be inferred if it falls within a firmly rooted hearsay exception or shows particular guarantees of trustworthiness.

In this case, Blackmun considered Isaacs’ testimony at the preliminary hearing to bear sufficient indicia of reliability. Although defense counsel did not formally cross-examine Isaacs, the questioning resembled cross-examination in form and purpose. The defense’s line of questioning challenged Isaacs’ veracity and explored the events underlying the charges, effectively testing her testimony as cross-examination would. Blackmun also found that the prosecution made a good-faith effort to secure Isaacs’ presence at trial. The prosecution issued multiple subpoenas to her last known address and discussed her whereabouts with her mother. He concluded that these efforts, although unsuccessful, satisfied the requirement of attempting to produce the witness.

Blackmun ultimately concluded that the admission of Isaacs’ preliminary hearing testimony did not violate Roberts’ Confrontation Clause rights. The testimony was deemed reliable, and the prosecution’s efforts to secure her presence met the constitutional standard of good faith. Thus, the Supreme Court of Ohio’s decision to reverse Roberts’ conviction was itself reversed, allowing the preliminary hearing testimony to be used in Roberts’ trial.

Dissenting Opinion by Justice Brennan

In his dissenting opinion, Justice William Brennan argued that the prosecution did not make a sufficient good-faith effort to locate Isaacs, thus failing the threshold requirement for unavailability under the Confrontation Clause of the Sixth Amendment.

Brennan emphasized the importance of the right to confront and cross-examine witnesses, which he described as an “essential and fundamental requirement for the kind of fair trial which is this country’s constitutional goal.” He pointed out that historically, the Confrontation Clause was intended to ensure that defendants could challenge their accusers directly before the jury, allowing the jury to assess the demeanor and credibility of witnesses before them. Despite the constitutional guarantee, Brennan acknowledged a limited exception for the use of prior testimony if the witness is unavailable. However, he argued that the prosecution bears a heavy burden to either secure the witness’ presence or demonstrate the impossibility of doing so. Brennan contended that in this case, the prosecution’s efforts were insufficient, as they consisted merely of delivering five subpoenas to Isaacs’ parents’ residence, even after learning she no longer lived there.

Brennan criticized the majority for excusing the prosecution’s inaction based on the improbability of success in locating Isaacs. He argued that mere speculation about the difficulty of finding a witness does not relieve the prosecution of its obligation to make a diligent effort. Brennan noted that the prosecution had enough information to at least initiate an investigation, such as contacting a San Francisco social worker who had been in touch with Isaacs.

In Brennan’s view, the prosecution's failure to pursue all obvious leads and make a bona fide search for Isaacs rendered the admission of her preliminary hearing testimony unconstitutional. He argued that the Constitution requires more than a perfunctory attempt to secure a witness’ presence and that the prosecution’s lack of effort in this case did not meet the standard of a good-faith effort necessary to satisfy the Confrontation Clause.