Salinas v. Texas

Case Overview

CITATION

ARGUED ON

DECIDED ON

DECIDED BY

570 U.S. 176 (2013)

April 17, 2013

June 17, 2013

Legal Issue

Does the Self-Incrimination Clause of the Fifth Amendment protect a defendant's right to refuse to answer questions from law enforcement before being arrested or read their Miranda rights?

Holding

No, the Self-Incrimination Clause of the Fifth Amendment does not protect the right of a defendant to refuse to answer questions before an arrest or before their Miranda rights have been read.

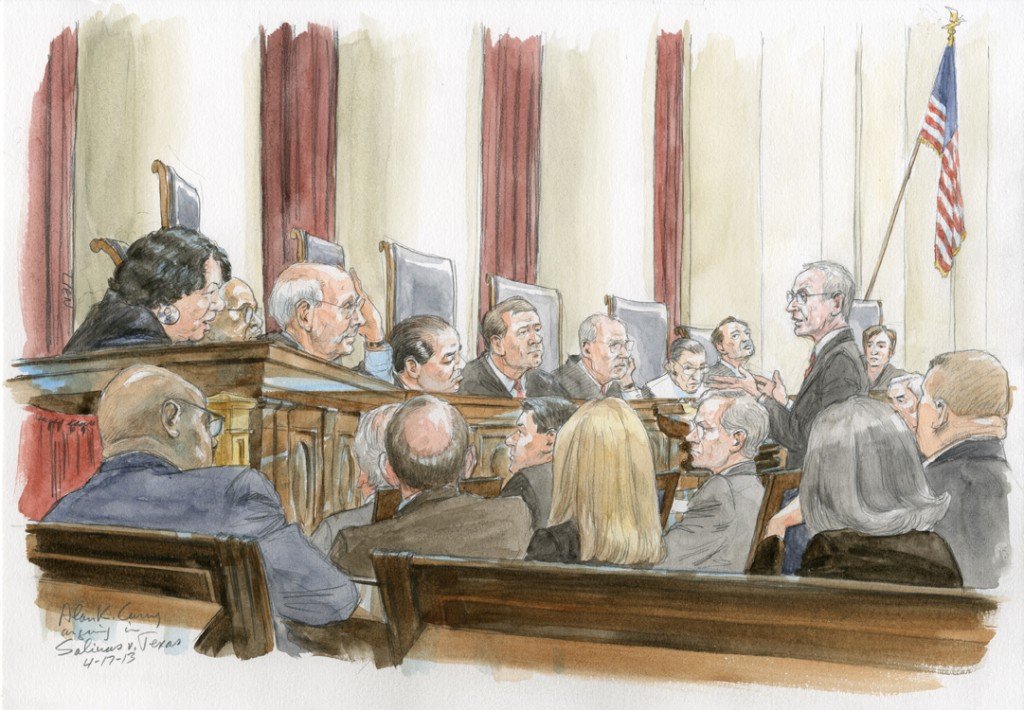

Assistant District Attorney Alan Curry arguing for respondent | Credit: SCOTUSblog

Background

In 1992, Houston police officers were questioning Genvevo Salinas as a suspect in two homicide cases. Salinas voluntarily went to the police station with the officers and answered their questions for about an hour. He was not arrested at that point. When officers asked him if the shotgun shells found at the scene of the homicides would match the gun at his home, Salinas didn’t respond and appeared to show signs of deception. After police found a witness who said that Salinas admitted to the homicides, a warrant for his arrest was issued. After 15 years, Salinas was caught and put on trial. His first trial ended in a mistrial, so the prosecutors tried to use his silence during questioning against him in his second trial. Salinas’ defense argued that this was a violation of his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination because it didn’t matter if he was in custody or not his rights were still protected. Salinas was found guilty at his second trial and sentenced to 20 years in prison and to pay a $5,000 fine. On appeal to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals and the Fourteenth Court of Appeals for Harris County Texas, Salinas’ conviction was upheld.

Summary

5 - 4 decision for Texas

Salinas

Texas

Sotomayor

Ginsburg

Kagan

Alito

Thomas

Breyer

Roberts

Scalia

Kennedy

Plurality Opinion by Justice Alito

Justice Samuel Alito, joined by Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Kennedy held that Salina’s claim that his Fifth Amendment rights were violated failed because he did not expressly invoke his right against self-incrimination during questioning. Alito began with a review of how the Fifth Amendment has historically been interpreted before the Court in a variety of cases and applications. He cited Garner v. United States (1976) to explain that “[t]he privilege against self-incrimination “is an exception to the general principle that the Government has the right to everyone’s testimony.” Elaborating this principle, Alito also cited Hoffman v. United States (1951), in which the Court held that the Fifth Amendment does not provide an “unqualified right to remain silent,” but rather protects the right to not be compelled as a witness against oneself in a criminal case. Alito also referenced the Court’s decision in Minnesota v. Murphy (1984) that established that a witness’ Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination is not self-executing. Alito further explained that this is important because it informs the government that a witness is relying on privilege, and it gives the Courts a reliable record to assess Fifth Amendment claims by.

Alito noted that there are two recognized exceptions to the requirement that a witness explicitly invoke their Fifth Amendment privilege. First, an individual does not need to take the stand at their own trial to assert their privilege, showing that the Fifth Amendment protects the “absolut right not to testify.” Second, an individual does not need to invoke their privilege when they are subjected to the “inherently compelling pressures” that are involved in a custodial interrogation. Established in Miranda v. Arizona (1966), this principle requires an individual to be “suitably warned” before they are required to explicitly invoke privilege.

Applying the principles of the Fifth Amendment to this case, Alito held that the circumstances could not support the allegation that Salinas’ rights were violated. Alito pointed out that Salinas went to the police station on his own accord, participated in the interview voluntarily, and was free to leave at any time. While Salinas was in an interrogation room at the police station with many characteristics of a custodial interrogation, nothing was preventing him from leaving or coercing him to stay, so it was Salinas’ responsibility to inform the officers that he was invoking privilege. Alito concluded, writing, “[s]o long as police do not deprive a witness of the ability to voluntarily invoke privilege, there is no Fifth Amendment violation.

Concurring Opinion by Justice Thomas

In his brief concurrence, Justice Clarence Thomas took a stricter view of the Fifth Amendment than the plurality. Thomas held that even if Salina had invoked his privilege, his claim would fail because the comments made by the prosecutor did not compel him to self-incriminate. Thomas explained that he disagreed with the Court’s decision in Griffin v. California (1965), which prohibited a prosecutor or a judge from using a witness’ failure to testify against them, because the history and tradition of English and American courts shows that defendants were encouraged to give unsworn statements and the courts drew “adverse inferences” when they didn’t. Thomas viewed Salinas’ petition as an attempt to extend the protection established in Griffin to beyond testimony in a courtroom, but he concluded that “[g]iven Griffin’s indefensible foundation, I would not extend it to a defendant’s silence during a precustodial interview.”