Stanley v. Georgia

Case Overview

CITATION

394 U.S. 557 (1969)

ARGUED ON

January 14-15, 1969

DECIDED ON

April 7, 1969

DECIDED BY

Legal Issue

Is a statute imposing criminal sanctions for the mere possession of obscene material constitutional under the First Amendment?

Holding

Yes. While obscenity is not a protected form of speech under the First Amendment, the government’s ability to regulate it does not extend into the privacy of an individual’s home.

Man viewing obscene material in a book | Source

Background

Law enforcement in Georgia obtained a warrant to search Robert Stanley’s home on the suspicion that he was a bookie for an illegal betting ring. The warrant instructed the officers to seize equipment, records, and other materials that may used in connection with an illegal betting business. While searching Stanley’s home, they found a set of adult films in a drawer and proceeded to view them on a projector in a room upstairs for about an hour. After seeing that they contained obscene content, the officers went downstairs and arrested Stanley under a Georgia obscenity statute. Stanley was tried and convicted, and his conviction was upheld by the Georgia Supreme Court.

Summary

Unanimous decision for Stanley

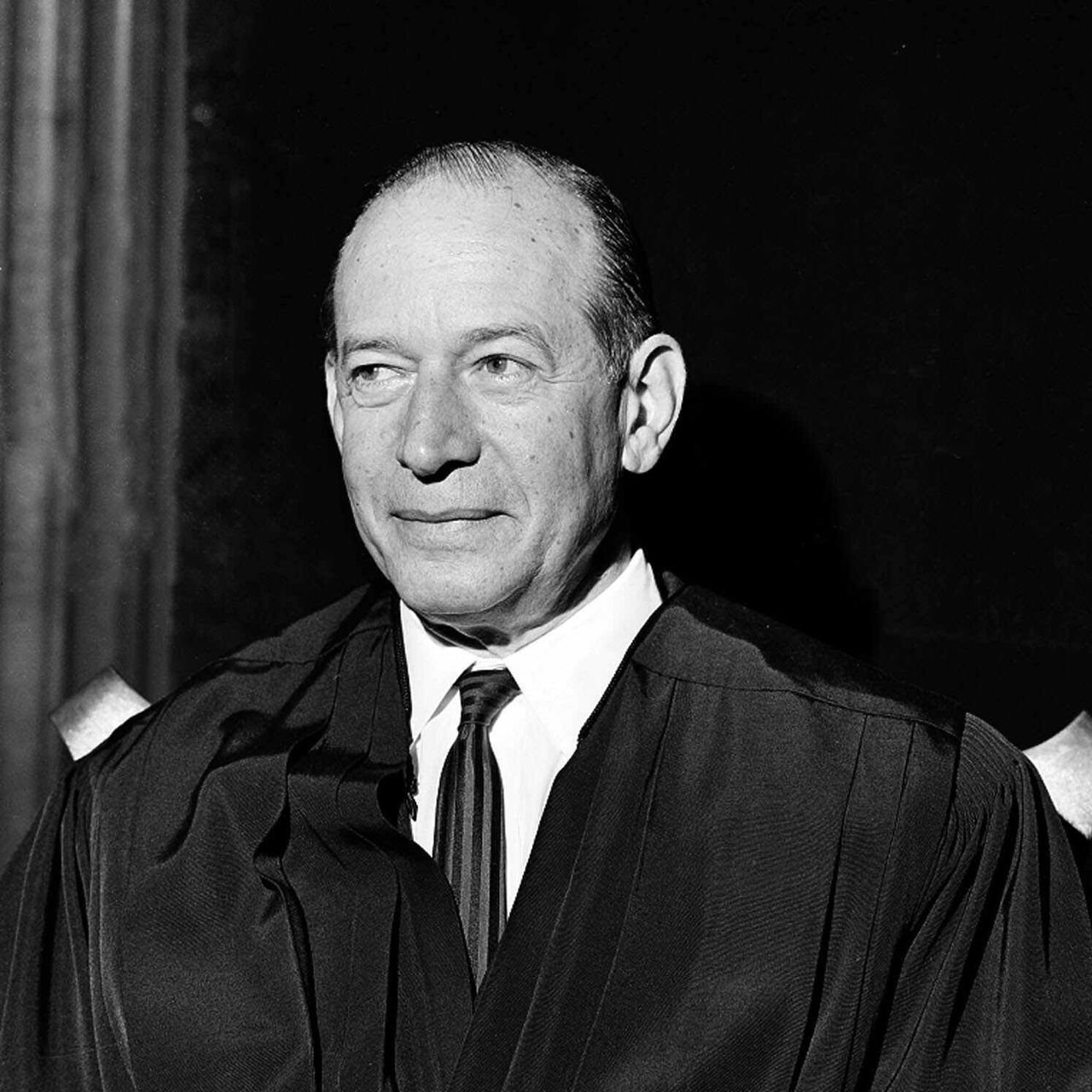

Stanley

Georgia

Warren

Black

White

Fortas

Brennan

Marshall

Stewart

Harlan

Douglas

Concurring Opinion by Justice Stewart

In his concurring opinion, Justice Potter Stewart, joined by Justices Brennan and White, focused on the implications of the case on the Fourth Amendment. Stewart argued that law enforcement had no right to seize the obscene films found in Stanley’s home because their search warrant stated that the place be searched with “particularity,” specifically for “equipment, records, and other material used in or derived from an illegal wagering business.”

Stewart explained that the purpose of the Fourth Amendment is to “guarantee to the people of this Nation that they should forever be secure from the general searches and unrestrained seizures that had been a hated hallmark of colonial rule under the notorious writs of assistance of the British Crown.” He further explained that law enforcement must obtain a search warrant that specifically outlines their authority in conducting a search. He cited the Court’s opinion in Marron v. United States (1927), in which it held that “[t]he requirement that warrants shall particularly describe the things to be seized makes general searches under them impossible and prevents the seizure of one thing under a warrant describing another.” Applying that standard to Stanley’s case, Stewart held that the obscene films were unlawfully obtained.

Stewart noted that this case does not impact the authority of law enforcement to perform a search incident to an arrest, but he concluded that “[t]o condone what happened here is to invite a government official to use a seemingly precise and legal warrant only as a ticket to get into a man's home, and, once inside, to launch forth upon unconfined searches and indiscriminate seizures as if armed with all the unbridled and illegal power of a general warrant.”

Concurring Opinion by Justice Black

In his brief concurrence, Justice Hugo Black agreed with the Court that the mere possession of obscene material cannot be criminalized and cited his previous writings in Smith v. California (1959) and Ginzburg v. United States (1966) as his reasoning.