Stromberg v. California

Case Overview

CITATION

283 U.S. 359 (1931)

ARGUED ON

April 15, 1931

DECIDED ON

May 18, 1931

DECIDED BY

Legal Issue

Did a state law that banned the display of red flags as a political statement violate the right to freedom of speech under the First Amendment?

Holding

Yes, the law violated the right to freedom of speech under the First Amendment.

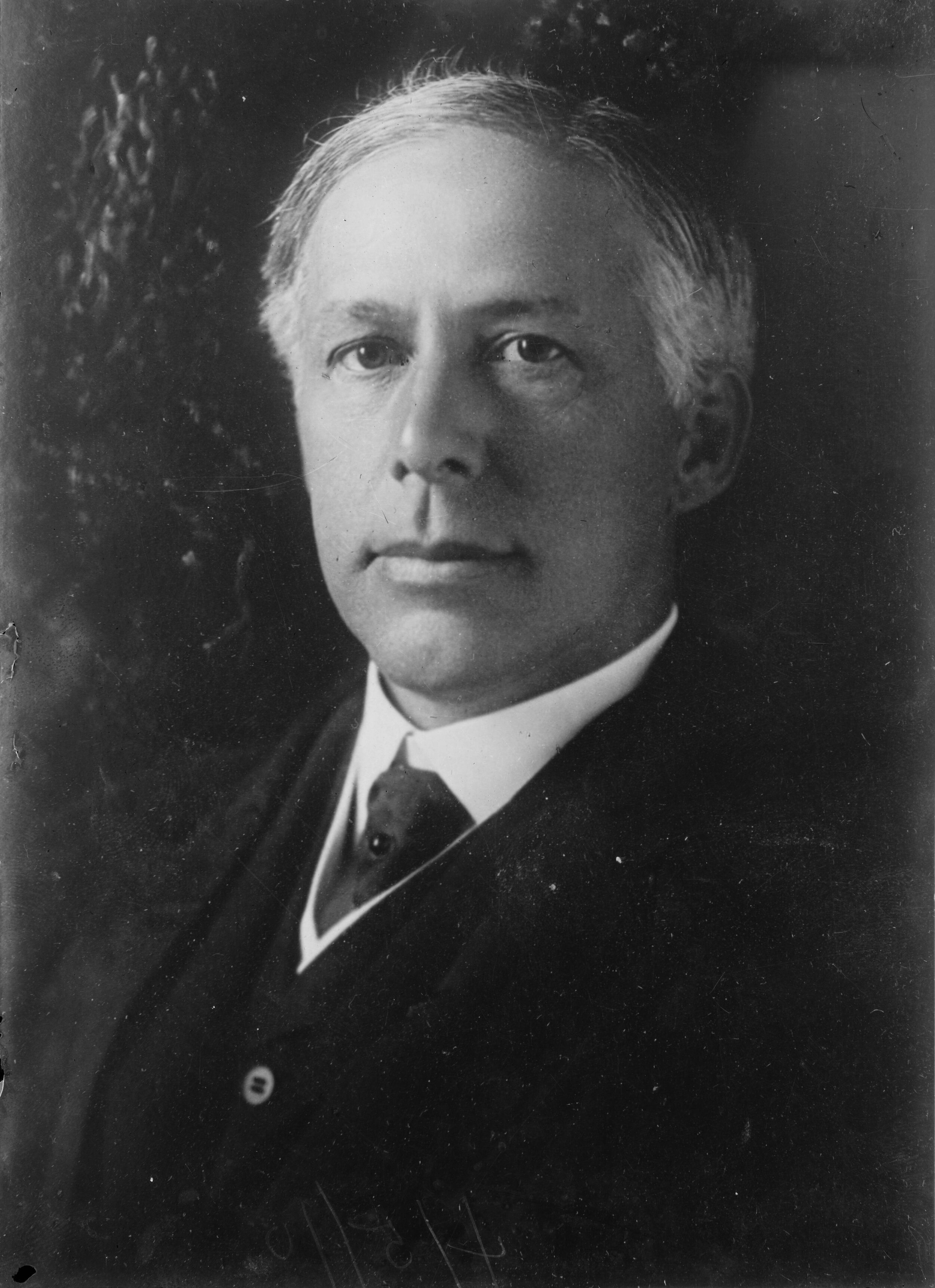

Yetta Stromberg | Credit: California Supreme Court Historical Society

Background

In 1919, California enacted Penal Code, §403(a), which read that:

“Any person who displays a red flag, banner or badge or any flag, badge, banner, or device of any color or form whatever in any public place or in any meeting place or public assembly, or from or on any house, building or window as a sign, symbol or emblem of opposition to organized government or as an invitation or stimulus to anarchistic action or as an aid to propaganda that is of a seditious character is guilty of a felony.”

In 1929, Yetta Stromberg was convicted of violating the California law after he raised a red flag at the Pioneer Summer Camp, a youth camp for working-class children that was run by Communist groups. At trial, Stromberg argued that the law violated the First Amendment as it applied to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment. The judge, however, overruled the objection and Stromberg was convicted by a jury.

Summary

7 — 2 decision for Stromberg

Stromberg

California

Hughes

Van Devanter

Holmes

Sutherland

Brandeis

Roberts

McReynolds

Stone

Butler

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Chief Justice Hughes held that California’s law was unconstitutional because it was too vague and too restrictive of free speech. Hughes acknowledged that the government has the right to limit speech in certain instances, writing that “[t]here is no question but that the State may thus provide for the punishment of those who indulge in utterances which incite to violence and crime and threaten the overthrow of organized government by unlawful means,” but that “[a] statute which upon its face, and authoritatively construed, is so vague and indefinite as to permit the punishment of the fair use of this opportunity is repugnant to the guaranty of liberty contained in the Fourteenth Amendment.”

Hughes found the section of the law which prohibited the display of a red flag as a “sign, symbol, or emblem of opposition to organized government” to be unconstitutional because it was too restrictive of free speech and it violated due process and under the Fourteenth Amendment. The other two provisions of the statute, which prohibited the flag’s display as an “invitation or stimulus to anarchistic action” or as an “aid to propaganda that is of a seditious character,” were both upheld as constitutional. On these provisions, Hughes reasoned that they served a legitimate government interest in protecting against incitements to violence. Despite the validity of two of the three provisions, Hughes reversed Stromberg’s conviction. This was also the first case in which the Court recognized constitutional protections for symbolic speech, such as Stromberg’s flag.

Dissenting Opinion by Justice McReynolds

In his dissenting opinion, Justice James McReynolds expressed that historically, the Court has consistently adhered to the principle that it should not review any issues stemming from a state court decision unless it has been clearly decided by the state court or appropriately presented for such a decision. In this particular case, there was no indication that such challenges had been raised. The Court of Appeals ruled that because the petitioner had been found guilty of violating all clauses of the statutes, the conviction could not be overturned even if one of the clauses was deemed unconstitutional. McReynolds concurred with this conclusion and recommended affirming the judgment.

Dissenting Opinion by Justice Brandeis

In his dissenting opinion, Justice Louis Brandeis disagreed with the Court’s ruling that declared the first clause, §403(a), of the California statute as invalid and overturned the state court’s decision due to its potential impact. Butler contended that the petitioner's conviction was not based on a violation of this specific clause, since the California Supreme Court had previously invalidated a city ordinance related to the display of certain symbols, implying the invalidity of the statute in cases concerning peaceful opposition to the government.

The jury was instructed that peaceful advocacy for governmental changes was protected, and any peaceful organization promoting such changes could freely choose its symbols. Despite these instructions, the defendant did not raise the issue of the first clause’s validity during the trial. Brandies pointed out that defense counsel also failed to object to the state’s instructions and expressed satisfaction with them in the Court of Appeals.

Justice Butler concluded that, in this case, the Court’s role did not involve determining the constitutional protection status of flag displays as a form of speech, assessing whether such speech fell under the shield of the Fourteenth Amendment, or evaluating if the potential chaos stemming from challenging established governance constituted a compelling enough basis to forbid such acts. Brandeis’ dissent largely focused on the procedural challenges of the case, rather than the questions to freedom of speech.