Tinker v. Des Moines

Case Overview

CITATION

393 U.S. 503 (1969)

ARGUED ON

November 12, 1968

DECIDED ON

February 24, 1969

DECIDED BY

Legal Issue

Does prohibiting the wearing of armbands in public school as a form of symbolic protest violate the First Amendment’s protection of the freedom of speech?

Holding

Yes, prohibiting students in public school from wearing an armband as a form of symbolic protest violates their First Amendment right to freedom of speech.

Mary Beth Tinker and her brother John | Credit: Bettmann/Getty Images

Background

On December 16, 1965, five students in the Des Moines Independent Community School District wore black armbands to school to protest the Vietnam war and show their support for the Christmas Truce that was called for by Senator Robert F. Kennedy. The principals of the Des Moines schools were informed about the protest beforehand and convened to establish a new policy. The new policy required students who wore an armband at school to take it off and any students found breaching the policy would face suspension until they agreed to adhere to the rule.

The students were promptly suspended according to the school district's recently implemented policy. Following their suspension, the students pursued nominal damages and requested an injunction against the policy. Despite the absence of any finding of substantial interference with school activities, the District Court dismissed their complaint on the grounds that the policy was within the school district’s power. Sitting en banc, the Court of Appeals affirmed the District Court’s decision.

Summary

7 — 2 decision for Tinker

Tinker

Des Moines

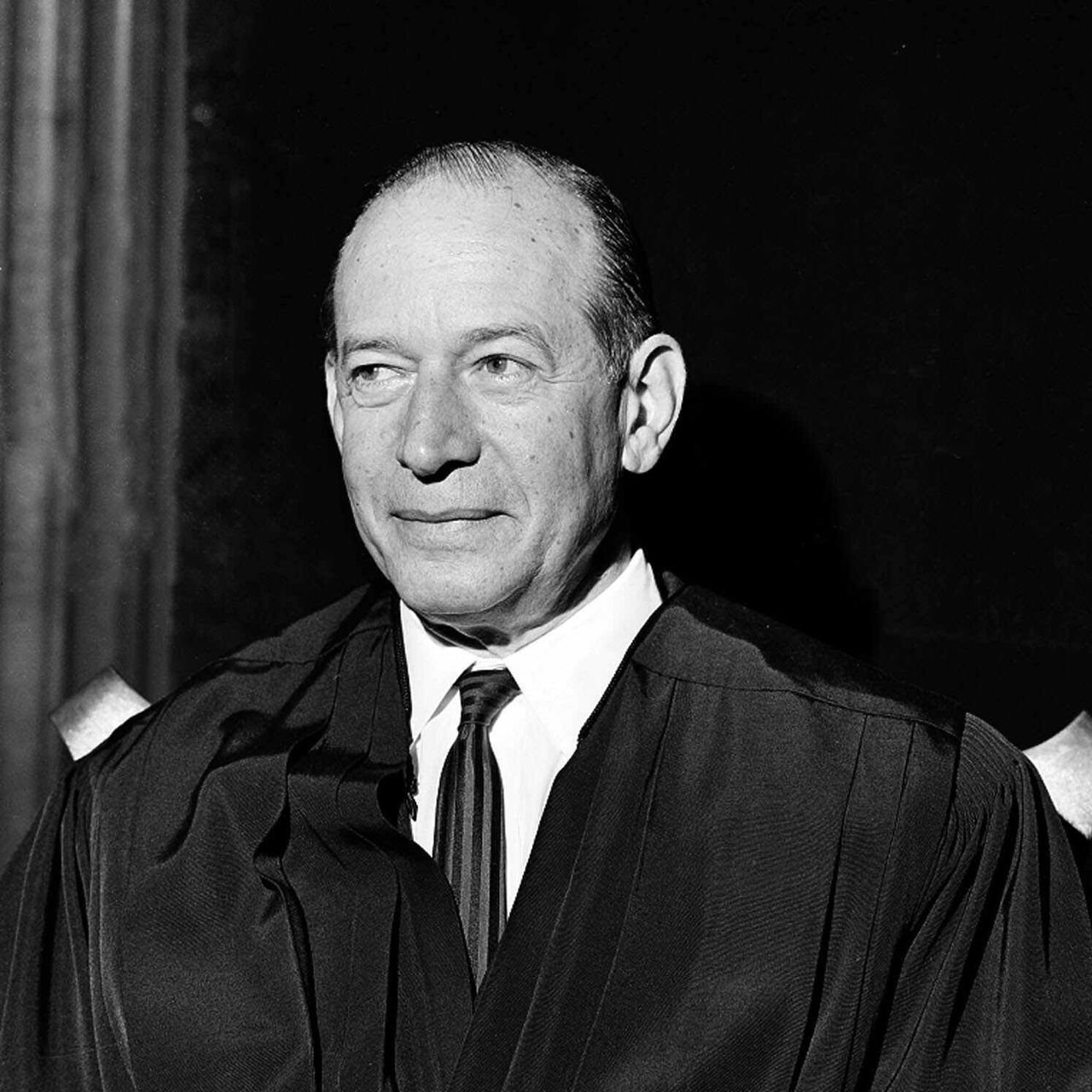

Warren

Harlan

Black

Douglas

Stewart

Brennan

Fortas

Marshall

White

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Justice Abe Fortas held that the school district’s policy prohibiting students from wearing black armbands violated the First Amendment’s protection of the freedom of speech. In response to the District Court’s finding that the school district’s fear of a disturbance caused by the armbands justified the burden placed on the students’ First Amendment right, Fortas wrote, “. . .in our system, undifferentiated fear or apprehension of disturbance is not enough to overcome the right to freedom of expression. Any departure from absolute regimentation may cause trouble. Any variation from the majority's opinion may inspire fear. Any word spoken, in class, in the lunchroom, or on the campus, that deviates from the views of another person may start an argument or cause a disturbance.”

Fortas argued that the freedom of speech is not bound by venue, and students and teachers retain their First Amendment rights even at school. He wrote, “It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” First Amendment rights are not absolute, however, but he explained that for a prohibition on speech to be justified, school officials must prove that “engaging in the forbidden conduct would ‘materially and substantially interfere with the requirements of appropriate discipline in the operation of the school.’”

In determining the case at hand, Fortas found the school district’s policy to be violative of the First Amendment because “the action of the school authorities appears to have been based upon an urgent wish to avoid the controversy which might result from the expression.” Furthermore, Fortas found that the students’ protest was “pure speech,” which the Court has repeatedly held is “entitled to comprehensive protection under the First Amendment.”

Fortas explained that students are free to express their opinions at school and placed limitations on the abilities of school officials to prohibit speech. He wrote, “In our system, state-operated schools may not be enclaves of totalitarianism. School officials do not possess absolute authority over their students. Students in school as well as out of school are ‘persons’ under our Constitution. They are possessed of fundamental rights which the State must respect, just as they themselves must respect their obligations to the State.”

“Under our Constitution, free speech is not a right that is given only to be so circumscribed that it exists in principle but not in fact. Freedom of expression would not truly exist if the right could be exercised only in an area that a benevolent government has provided as a safe haven for crackpots. The Constitution says that Congress (and the States) may not abridge the right to free speech. This provision means what it says. We properly read it to permit reasonable regulation of speech-connected activities in carefully restricted circumstances. But we do not confine the permissible exercise of First Amendment rights to a telephone booth or the four corners of a pamphlet, or to supervised and ordained discussion in a school classroom.”

— Justice Abe Fortas

Concurring Opinion by Justice Stewart

In his brief concurrence, Justice Potter Stewart notes that he agrees with much of the Court’s opinion, but he “cannot share the Court's uncritical assumption that, school discipline aside, the First Amendment rights of children are co-extensive with those of adults.” He further explained his view by quoting his opinion in Ginsberg v. New York (1968), in which he wrote that “[A] State may permissibly determine that, at least in some precisely delineated areas, a child-like someone in a captive audience-is not possessed of that full capacity for individual choice which is the presupposition of First Amendment guarantees.”

Concurring Opinion by Justice White

In his brief concurrence, Justice Byron White noted that “the Court continues to recognize a distinction between communicating by words and communicating by acts or conduct which sufficiently impinges on some valid state interest.”

Dissenting Opinion by Justice Harlan

In his brief dissent, Justice John Harlan II agreed with the Court’s finding that school officials “are not wholly exempt from the requirements of the Fourteenth Amendment respecting the freedoms of expression and association,” but he found “nothing in this record which impugns the good faith of respondents in promulgating the armband regulation.”

Dissenting Opinion by Justice Black

In his dissent, Justice Hugo Black disagreed with the Court’s finding that the school district did not have a legitimate justification for the restriction of the students’ “symbolic speech” by prohibiting them from wearing armbands. He wrote, “While the absence of obscene remarks or boisterous and loud disorder perhaps justifies the Court's statement that the few armband students did not actually ‘disrupt’ the classwork, I think the record overwhelmingly shows that the armbands did exactly what the elected school officials and principals foresaw they would, that is, took the students' minds off their classwork and diverted them to thoughts about the highly emotional subject of the Vietnam war.”

Black also disagreed with the Court’s expansive view of student rights and stated that “if the time has come when pupils of state-supported schools, kindergartens, grammar schools, or high schools, can defy and flout orders of school officials to keep their minds on their own schoolwork, it is the beginning of a new revolutionary era of permissiveness in this country fostered by the judiciary.” While reaffirming his belief in the freedom of speech, Black noted that he this does not mean that any person “has a right to give speeches or engage in demonstrations where he pleases and when he pleases.”

Furthermore, Black explained that school officials are permitted to place limitations on the speech of teachers and students, writing that “[t]he truth is that a teacher of kindergarten, grammar school, or high school pupils no more carries into a school with him a complete right to freedom of speech and expression than an anti-Catholic or anti-Semite carries with him a complete freedom of speech and religion into a Catholic church or Jewish synagogue.” He noted that schools “are operated to give students an opportunity to learn, not to talk politics by actual speech, or by ‘symbolic’ speech.”

Black warned that the Court’s decision would have dangerous ramifications on the authority of school officials and the values of the public school system. He wrote, “[u]ncontrolled and uncontrollable liberty is an enemy to domestic peace. We cannot close our eyes to the fact that some of the country's greatest problems are crimes committed by the youth, too many of school age. School discipline, like parental discipline, is an integral and important part of training our children to be good citizens-to be better citizens. . . One does not need to be a prophet or the son of a prophet to know that after the Court's holding today some students in Iowa schools and indeed in all schools will be ready, able, and willing to defy their teachers on practically all orders.”