United States v. Wong Kim Ark

Case Overview

CITATION

ARGUED ON

DECIDED ON

169 U.S. 649

March 5, 8, 1897

March 28, 1898

DECIDED BY

Legal Issue

Is a child born in the United States to Chinese- citizen parents a U.S. citizen under the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment?

Holding

Yes, the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment grants U.S. citizenship to all who are born within the United States with only a few exceptions.

A photograph of Wong Kim Ark from a U.S. immigration document in 1904 | Credit: Creative Commons

Background

Wong Kim Ark was born in San Francisco in 1873 to Chinese parents who were subjects of the Emperor of China but resided in the United States. Although Wong was born on U.S. soil, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and subsequent laws significantly restricted immigration from China and the rights of Chinese immigrants, raising questions about the citizenship status of their U.S.-born children.

In 1894, after a trip to China, Wong was denied reentry into the United States by customs officials, who argued that he was not a U.S. citizen because his parents were subjects of the Chinese Emperor and not U.S. citizens. Wong challenged this decision, arguing that under the Fourteenth Amendment, which grants citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof,” he was a citizen by birthright.

The case progressed through the lower courts, where judges ruled in Wong’s favor, stating that his birthplace within the U.S. entitled him to citizenship. However, the U.S. government appealed the decision to the Supreme Court, who ultimately granted certiorari.

Summary

6 - 2 decision for Wong Kim Ark

U.S.

Wong Kim Ark

* Justice McKenna took no part in the consideration or decision of this case.

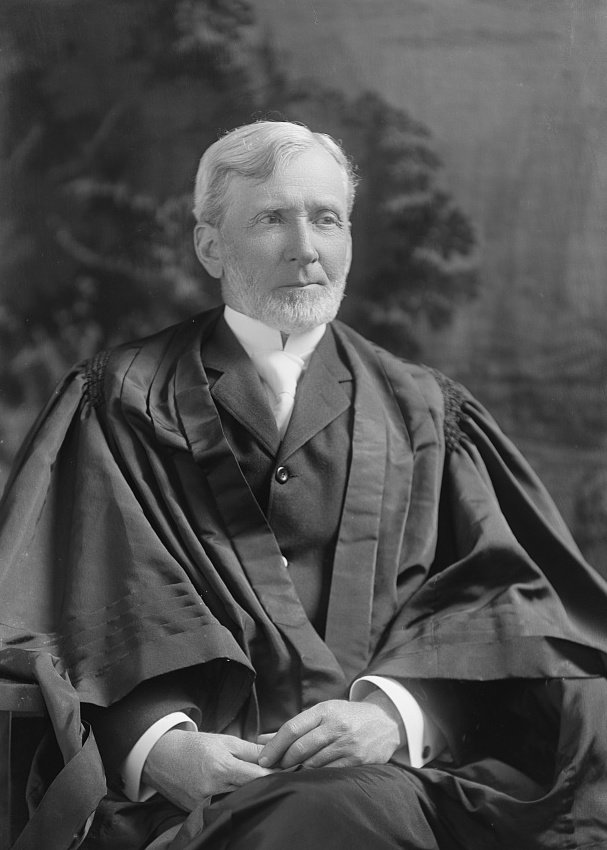

Shiras

Brown

Gray

Fuller

White

Brewer

McKenna*

Harlan

Peckham

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Justice Horace Gray held that Wong Kim Ark was a U.S. citizen based on the principle of jus soli, or right of the soil, as established by the Fourteenth Amendment. Gray emphasized that the Fourteenth Amendment establishes that, “[a]ll persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” This phrase, “subject to the jurisdiction thereof”, according to Gray, was a clear affirmation of the principle of jus soli, and excluded only the children of foreign rulers or diplomats, those born on foreign public ships, the children of enemy forces engaged in hostile occupation of the U.S., and Indian tribes not taxed by the U.S.

In applying these principles to Wong Kim Ark, Gray stated that, “[t]he Constitution nowhere defines the meaning of these words, either by way of inclusion or of exclusion... it must be interpreted in the light of the common law, the principles and history of which were familiarly known to the framers of the Constitution.” Reviewing the historical and legal precedents, Gray explained that the rule of citizenship by birthplace had been long recognized both in English common law and in early American law. He explained that under English common law, all persons born within the allegiance of the King were subjects, and this concept was carried over to the American colonies and later the United States.

Gray dismissed the argument that the citizenship of a child followed that of the parent, emphasizing that the Fourteenth Amendment’s intent was to grant citizenship to all born on U.S. soil, regardless of their parent’s status. He cited the historical context of the Fourteenth Amendment, noting that it was intended to overrule the Dred Scott v. Sandford decision, which had denied citizenship to African Americans. Gray ultimately concluded that Wong Kim Ark was a citizen by virtue of his birth in the United States, upholding the principle that birth within U.S. territory confers citizenship.

Dissenting Opinion by Chief Justice Fuller

In his dissenting opinion, Chief Justice Melville Fuller argued that the majority's ruling misinterpreted the constitutional and historical basis for determining U.S. citizenship, particularly with regard to the children of foreign nationals born on U.S. soil. Fuller contended that the Fourteenth Amendment’s phrase “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” did not simply mean being within U.S. territory but required complete political allegiance to the United States. He argued that the framers of the Amendment intended to exclude from citizenship the children of foreign nationals who were merely temporarily in the country.

Fuller pointed out that under English common law, allegiance was a key factor in determining citizenship, and mere birth within the territory was insufficient. Fuller asserted that the United States, as a sovereign nation, had the right to define the criteria for its citizenship, including the exclusion of children born to foreign nationals who had no permanent allegiance to the U.S. He cited the Slaughter-House Cases (1873) to support his interpretation that the jurisdiction requirement of the Fourteenth Amendment was meant to exclude those who owed allegiance to a foreign power.

Furthermore, Fuller criticized the majority's reliance on the common law principle of jus soli, arguing that the United States had not uniformly followed this principle and that its application was inconsistent with the nation’s status as a sovereign entity with the power to control its own membership. Fuller also expressed concern about the practical implications of the majority's decision, suggesting that it could lead to an influx of foreigners seeking to secure U.S. citizenship for their children merely by giving birth on American soil. He feared this would undermine the country’s ability to regulate its own population and citizenship requirements. He ultimately concluded that the Fourteenth Amendment’s citizenship clause was not intended to grant automatic citizenship to the children of foreign nationals born in the U.S.