United States v. O’Brien

Case Overview

CITATION

391 U.S. 367 (1968)

ARGUED ON

January 24, 1968

DECIDED ON

May 27, 1968

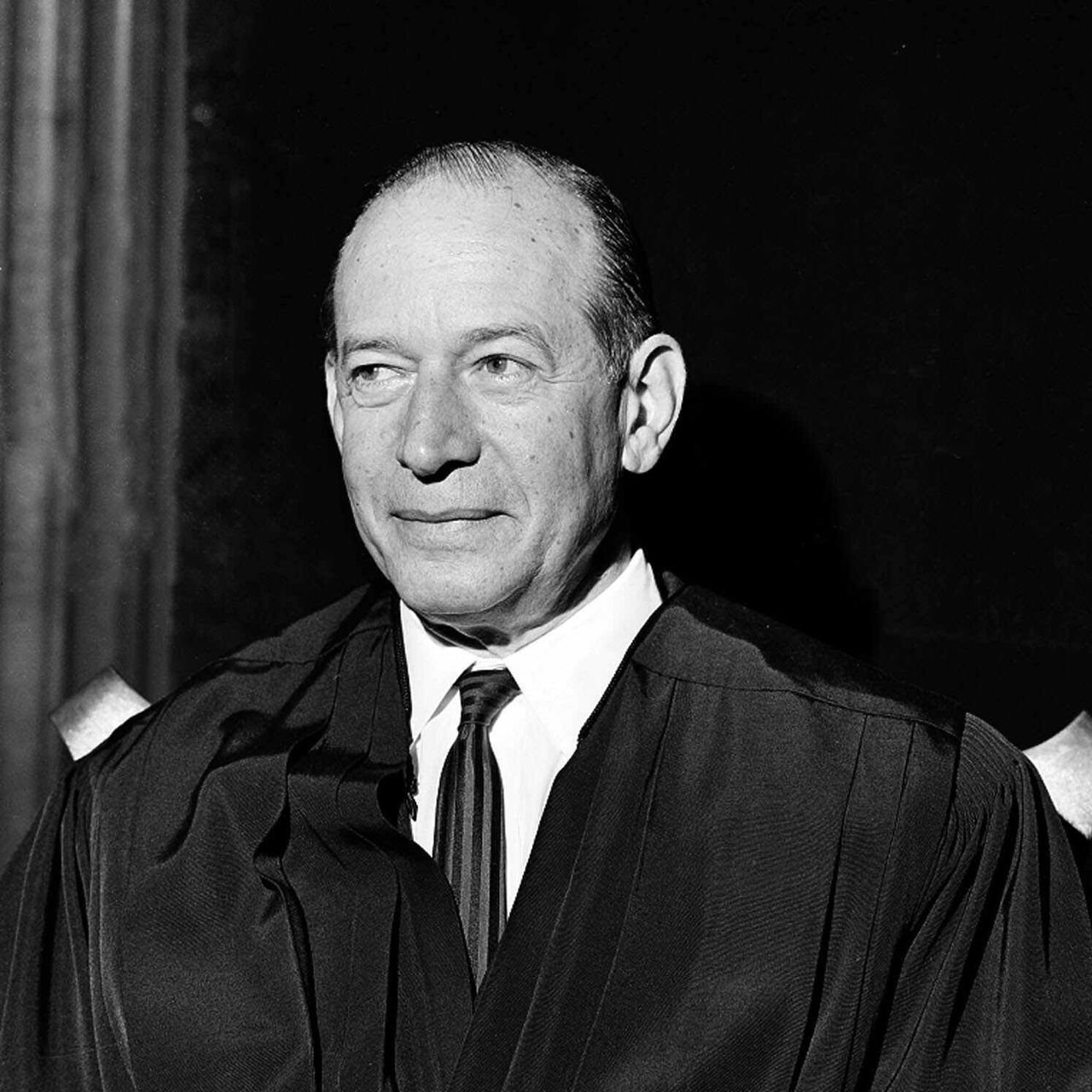

DECIDED BY

Legal Issue

Did Congress’ 1965 amendment to the Selective Service Act, which prohibited the willful destruction of draft cards, violate the right to freedom of speech protected by the First Amendment?

Holding

No. The speech targeted was incidental to the government’s significant interest in maintaining an efficient and effective military draft system.

O’Brien burning his draft card on March 31, 1966 | Credit: Bettman/Getty Images

Background

During the Vietnam War, the destruction of draft cards became a popular form of protest against the war. In 1965, Congress amended the Selective Service Act to prohibit the willful destruction of draft cards.

On March 31, 1966, David O’Brien burned his draft card on the steps of the South Boston Courthouse in front of a crowd as a form of protest, which included several FBI agents who subsequently arrested O’Brien. At trial, O’Brien represented himself and explained to the jury that he burned his draft card in protest "so that other people would reevaluate their positions with Selective Service, with the armed forces, and reevaluate their place in the culture of today, to hopefully consider my position.” O’Brien was ultimately found guilty by the jury, but his conviction was overturned by the First Circuit Court of Appeals before reaching the Supreme Court.

Summary

7 — 1 decision for the United States

United States

O’Brien

White

Harlan

Black

Stewart

Fortas

Warren

Douglas

Brennan

* Marshall

* Justice Marshall took no part in the consideration or decision of this case.

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Chief Justice Earl Warren held that the law prohibiting the willful destruction of draft cards did not violate the right to free speech because it was content-neutral and narrowly targeted to achieve a substantial government interest. Although O’Brien argued that the law was passed only to stifle the free speech of anti-war protestors, Warren reasoned that Congress’ supposed intention did not matter so long as the law could be justified on another basis, stating that “this Court will not strike down an otherwise constitutional statute on the basis of an alleged illicit legislative motive.”

Warren found that in determining the constitutionality of a statute that prohibits conduct including elements of speech and non-speech, the government must have a substantially important interest in regulating the non-speech element to justify the abridgment of the freedom of speech. To measure this, Warren found that a law is “sufficiently justified” if it meets the following criteria:

The law is within the constitutional power of the government

The law furthers an important or substantial government interest

The government’s interest is unrelated to the suppression of free expression

The law restricts no more speech than necessary to achieve the government's interest.

Warren concluded that the law prohibiting the willful destruction of draft cards met each of these criteria and was thus constitutional.

Dissenting Opinion by Justice Douglas

In his brief dissent, Justice William Douglas agreed with the Court’s holding that the military but believed that “[t]he underlying and basic problem in this case, however, is whether conscription is permissible in the absence of a declaration of war.” Douglas did not comment specifically on the Court’s ruling but believed that the case should have been reargued on that question.