Williams v. Florida

Case Overview

CITATION

399 U.S. 78 (1970)

ARGUED ON

March 4, 1970

DECIDED ON

June 22, 1970

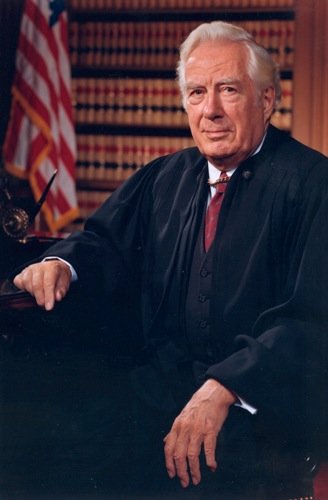

DECIDED BY

Legal Issue

Does the right against self-incrimination excuse a defendant from giving the prosecution notice of the identities of their alibi witnesses?

Does the Sixth Amendment require a jury in a criminal trial be composed of 12 members?

Holding

No, the right to self-incrimination does not excuse a defendant from giving the prosecution notice of the identities of their alibi witnesses.

No, the Constitution does not require that juries be composed of 12 members.

Jesse McRary, then the Assistant Attorney General of Florida, argued the case before the Supreme Court on behalf of the respondent

Background

Joe L. Williams was charged with robbery in Florida. During his trial, Williams was compelled by Florida Procedural Rule 1.200 to notify the prosecution of any alibi defense he planned to use, including specific details about where he was at the time of the robbery and the names of witnesses who could corroborate his claim. Williams challenged this rule, arguing that it violated his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination and his Sixth Amendment right to a fair trial by effectively forcing him to disclose his defense strategy to the prosecution. Additionally, in 1967, Florida reduced the number of jurors in non-capital criminal cases from 12 to 6, Williams also challenged this rule, arguing that the Sixth Amendment required a jury of 12 members.

Williams was tried, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison. He appealed, asserting that the disclosure requirement placed an unfair burden on defendants and could be used against them in a manner that was prejudicial and contrary to the principles of justice. Florida District Court of Appeals upheld his conviction, and the Supreme Court subsequently granted certiorari.

Summary

7 - 1 decision for Florida

Williams

Florida

Black

Douglas

Marshall

Stewart

Burger

Harlan II

Brennan

White

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Justice Byron White held that both Florida's notice-of-alibi rule and the state's use of six-member juries in non-capital cases were constitutional. Addressing the claim that the notice-of-alibi rule violated the Fifth Amendment's protection against self-incrimination, White argued that the rule did not compel the defendant to testify or incriminate himself but merely accelerated the timing of disclosure of the defense. He then turned to the issue of jury size, addressing whether the Sixth Amendment required juries to consist of exactly twelve members. Noting the historical context, he acknowledged that while twelve-member juries were traditional, there was no specific constitutional requirement for this number. He emphasized the importance of the jury's role in preventing government oppression and ensuring community participation in the judicial process, but argued that these functions were not dependent on the number of jurors, stating, “[t]he 12-man requirement cannot be regarded as an indispensable component of the Sixth Amendment.”

White also pointed out that the essential feature of a jury is its ability to deliberate and represent a cross-section of the community. He argued that a six-member jury could adequately fulfill these purposes, noting that there was no evidence to suggest that smaller juries were less effective in reaching fair verdicts. He ultimately found that a six-member jury was not unconstitutional, stating, “[w]e do not pretend that the 12-man jury is necessarily better or worse than one of smaller size, but the Constitution does not require that the jury must be composed of exactly 12 members.”

Concurring Opinion by Chief Justice Burger

In his concurring opinion, Chief Justice Warren Burger agreed with the majority’s reasoning but wrote separately to highlight the potential for the rule to improve the efficiency of the criminal justice system by encouraging pretrial disclosure and reducing unnecessary trials. He argued that the notice-of-alibi rule could lead to the resolution of cases without the need for a trial in situations where the evidence clearly supported the defendant’s alibi, stating, “[t]he prosecutor upon receiving notice will, of course, investigate prospective alibi witnesses. If he finds them reliable and unimpeachable, he will doubtless re-examine his entire case, and this process would very likely lead to the dismissal of the charges.” On the other hand, Burger noted that by requiring pretrial disclosure of alibi witnesses, the rule would allow the prosecution to investigate and potentially impeach false alibi claims, explaining that, “[i]nquiry into a claimed alibi defense may reveal it to be contrived and fabricated, and the witnesses accordingly subject to impeachment or other attack.”

Burger argued that reciprocal pretrial disclosure would shift the criminal justice system away from a competitive mentality, where each side aims to surprise the other, towards a more transparent and fair process. He concluded, “[t]hese are the likely consequences of an enlarged and truly reciprocal pretrial disclosure of evidence and the move away from the ‘sporting contest’ idea of criminal justice.”

Dissenting Opinion by Justice Harlan II

In his dissenting opinion, Justice John Harlan II expressed strong disagreement with the majority’s decision that a six-member jury satisfies the Sixth Amendment. He argued that the Court’s ruling departed from historical precedent and the original intent of the framers.

Harlan argued that the Sixth Amendment’s guarantee of a jury trial should be understood as including the common-law requirement of a twelve-member jury. He referenced the longstanding judicial understanding that the Constitution preserved this feature of the common-law jury and cited previous cases where the Court had consistently interpreted the Sixth Amendment to include a jury composed of twelve individuals. He argued that the states were bound by this tradition, stating that “[t]he decision evinces, I think, a recognition that the ‘incorporationist’ view of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment…must be tempered to allow the States more elbow room in ordering their own criminal systems.”

Harlan criticized the Court for relying on a historical analysis that he found inadequate to support the conclusion that a twelve-member jury was not essential. He contended that the framers of the Constitution intended to preserve the key features of the common-law jury, which included its size. Harlan argued that the Court’s historical justification was “much too thin to mask the true thrust of this decision” and that the decision “strangely does an about-face” by deviating from established precedents that had affirmed the necessity of a twelve-member jury.

Harlan also addressed the implications of the Court’s decision on the incorporation doctrine, which applies the Bill of Rights to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment. He contended that the incorporation doctrine should not lead to a dilution of constitutional protections, but rather should ensure that states adhere to the same rigorous standards as the federal government. Harlan concluded that the decision represented a departure from the proper understanding of the Sixth Amendment and a troubling shift in the Court’s approach to constitutional interpretation     .