Baldwin v. New York

Case Overview

CITATION

399 US 66 (1970)

ARGUED ON

December 9, 1969

DECIDED ON

June 22, 1970

DECIDED BY

Legal Issue

Does the Sixth Amendment right to a jury trial apply to defendants charged with offenses that carry a potential penalty of more than six months of incarceration?

Holding

Yes, offenses punishable by imprisonment for more than six months are considered serious and thus require the right to a jury trial under the Sixth Amendment, as applied to the states by the Fourteenth Amendment.

A New York City Police Officer pictured for a series of “life on the beat” photos in the 1970s | Credit: Leonard Freed/FLASHBAK

Background

Robert Baldwin was charged with attempted petit larceny and jostling in New York, misdemeanor charges that, under the applicable state law at the time, could be tried without a jury if the maximum sentence did not exceed six months. Baldwin's case, however, involved potential penalties that could cumulatively exceed six months of imprisonment due to the charges being tried together.

Baldwin requested a jury trial, but his request was denied based on state law. He was subsequently tried in a non-jury trial in the Criminal Court of the City of New York and was convicted. He was sentenced to concurrent terms of one year for each offense.

Following his conviction, Baldwin appealed the denial of his jury trial request, arguing that his constitutional right to a jury trial was violated due to the combined potential sentences for the charges against him, which together amounted to more than six months. His appeals in state courts were unsuccessful; the higher courts held that since each individual charge did not carry a sentence exceeding six months, the jury trial right did not apply, even if the aggregate sentence might exceed that duration. The Supreme Court ultimately granted certiorari.

Summary

5 - 3 decision for Baldwin

Baldwin

New York

Black

Douglas

Marshall

Harlan II

Stewart

Brennan

Burger

White

Opinion of the Court

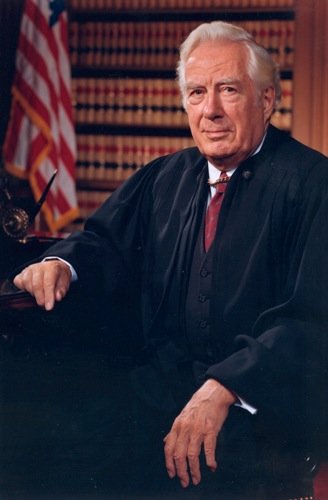

Writing for the majority, Justice Byron White held that offenses punishable by imprisonment for more than six months are considered serious and thus require the right to a jury trial under the Sixth Amendment, as applied to the states by the Fourteenth Amendment.

White began by referencing the Court’s decision in Duncan v. Louisiana (1968), which held that the Sixth Amendment guarantees the right to a jury trial in serious criminal cases, a right extended to state courts through the Fourteenth Amendment. He reiterated that while petty offenses could be tried without a jury, the challenge was to define what constituted a “serious” offense, stating, “[i]n deciding whether an offense is ‘petty,’ we have sought objective criteria reflecting the seriousness with which society regards the offense, and we have found the most relevant such criteria in the severity of the maximum authorized penalty.” Applying this standard, White concluded that an offense punishable by more than six months imprisonment could not be considered petty and emphasized that the possibility of a one-year sentence made the offense serious enough to warrant a jury trial. He stated, “[n]o offense can be deemed ‘petty’ for purposes of the right to trial by jury where imprisonment for more than six months is authorized.”

White rejected New York’s argument that the line between petty and serious offenses should align with the distinction between misdemeanors and felonies, where misdemeanors are punishable by up to one year and felonies by longer terms, stating that some misdemeanors, like Baldwin’s offense, are also serious. He highlighted the importance of societal norms and legal practices across the nation, pointing out that most states and the federal government provided jury trials for offenses punishable by more than six months' imprisonment. White also emphasized that the primary purpose of the jury trial is to prevent government oppression by ensuring that the accused’s fate is determined by their peers rather than government officials. He concluded that New York City’s practice of denying jury trials for offenses punishable by up to one year in prison was inconsistent with the constitutional guarantee of a jury trial for serious offenses.

Concurring Opinion by Justice Black

In his concurring opinion Justice Hugo Black agreed with the majority’s ruling but emphasized a broader interpretation of the Sixth Amendment and the historical context of jury trials. Black diverged from the majority by rejecting the distinction between “petty” and “serious” offenses, stating that “[t]he Constitution guarantees a right of trial by jury in two separate places but in neither does it hint of any difference between ‘petty’ offenses and ‘serious’ offenses.’” He pointed to the Constitution's explicit language, which guarantees a jury trial in “all criminal prosecutions” and for “all crimes.” He also criticized past decisions that introduced the distinction between petty and serious crimes, arguing that such judicial amendments contradicted the clear intent of the Constitution's framers. Black asserted, “[t]hose who wrote and adopted our Constitution and Bill of Rights engaged in all the balancing necessary. They decided that the value of a jury trial far outweighed its costs for ‘all crimes’ and ‘[i]n all criminal prosecutions.’”

Black expressed his disapproval of the Court's attempt to reassess the balance between the advantages of a jury trial and the administrative inconvenience to the state, which led to arbitrary decisions like setting the threshold at six months imprisonment. He argued that such decisions amounted to “judicial mutilation of our written Constitution,” and emphasized that the only legitimate way to change this balance was through the constitutionally prescribed method of amendment.

Dissenting Opinion by Chief Justice Burger

In his dissenting opinion, Chief Justice Warren Burger argued against the majority’s decision to mandate jury trials for offenses punishable by more than six months of imprisonment, emphasizing a historical and practical perspective and underscoring the importance of state discretion in the context of federal versus state authority. He acknowledged the Sixth Amendment’s guarantee of a jury trial in “all criminal prosecutions” and Article III’s guarantee for “all crimes,” but argued that these provisions were originally intended as limitations on federal power rather than commands to the states. He highlighted the limited scope of federal criminal law at the time the Constitution was drafted, pointing out that federal offenses were “very grave and few in number” and primarily concerned with federal authority.

Burger criticized the majority for extending federal standards to the states, suggesting that the Constitution’s framers did not intend to impose uniform criminal procedures across diverse states. He expressed concern about the increasing tendency to demand uniformity in legal standards, which he believed undermined the principle of federalism. He stated, “I see no reason why an infinitely complex entity such as New York City should be barred from deciding that misdemeanants can be punished with up to 365 days confinement without a jury trial while in less urban areas another body politic would fix a six-month maximum for offenses tried without a jury.” He argued that the decision to classify crimes and determine appropriate punishments, including the availability of jury trials, should be left to the states and emphasized that different regions might have different views on what constitutes a serious offense and how it should be adjudicated. Burger concluded that the near-uniform judgment of the nation regarding the seriousness of offenses did not justify imposing a rigid standard on all states. Instead, he advocated for respecting the flexibility and discretion of state legislatures in administering their criminal justice systems.