Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc.

Case Overview

CITATION

418 U.S. 323 (1974)

ARGUED ON

November 14, 1973

DECIDED ON

June 25, 1974

DECIDED BY

Legal Issue

Does a private individual need to prove “actual malice” to sue a media publication for defamatory statements?

Holding

No, the First Amendment does not require the “actual malice” standard for defamation of private individuals.

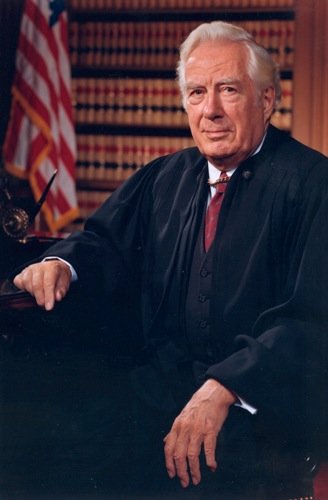

Robert Welch Jr. on June 25, 1961 | Credit: Bill Johnson/Denver Post Archive/Getty Images

Background

In 1968, Chicago police officer Richard Nuccio was convicted of second-degree murder after he shot and killed Ronald Nelson. Nelson's family retained a lawyer, Elmer Gertz, to represent them in civil litigation against the officer.

In March 1969, the John Birch Society published an article in the American Opinion magazine titled “FRAME-UP: Richard Nuccio and the War on Police”, which claimed that the testimony against Nuccio at his criminal trial was false and that his prosecution was part of the Communist campaign against the police. The article also claimed that Nelson had a criminal record, that he had taken part in the 1968 Chicago riots, and that he was a Leninist or “Communist-fronter” with membership in the Marxist League for Industrial Democracy or the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Each of these claims were false, but the managing editor of the magazine made no effort to verify or substantiate the claims made against Nelson.

Gertz sued the magazine for libel on behalf of Nelson’s family and a jury awarded him a verdict of $50,000. However, the trial judge overturned the jury verdict, since the magazine had not violated the “actual malice” standard established in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964). Gertz appealed, but the Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit affirmed the trial judge’s ruling.

Summary

7 - 2 decision for Gertz

Gertz

Welch

Burger

Rehnquist

Blackmun

Douglas

Stewart

Brennan

Powell

Marshall

White

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the majority, Justice Louis Powell held that “so long as they do not impose liability without fault, the States may define for themselves the appropriate standard of liability for a publisher or broadcaster of defamatory falsehood injurious to a private individual.” He also acknowledged the inevitability of falsehoods in free debate, writing “[a]lthough the erroneous statement of fact is not worthy of constitutional protection, it is nevertheless inevitable in free debate. . . The First Amendment requires that we protect some falsehood in order to protect speech that matters.”

Powell noted that the core state interest behind libel laws is to compensate individuals for the harm caused by defamatory falsehoods. This introduces a tension between the need for a vigorous press and the interest in redressing wrongful harm. Powell pointed to the rule established in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), which balanced concerns about a free press with the limited state interest in libel actions brought by public figures, and contrasted this with the heightened state interest in protecting private individuals. Private individuals, Powell observed, have not assumed the risk of defamatory falsehoods to the same extent as public figures and are consequently more vulnerable to harm. Therefore, the state has a greater interest in compensating and protecting private individuals from defamation. Powell concluded that a different liability standard is justified for private individuals to adequately protect their reputations while also accommodating First Amendment freedoms.

Concurring Opinion by Justice Blackmun

In his brief concurrence, Justice Blackmun wrote that while while he joined the Court’s opinion, he only did so to form a majority opinion (Chief Justice Burger and Justice White also dissented in part on what type of liability states could impose on media publications but concurred on the primary question of “actual malice”). He explained, “it is of profound importance for the Court to come to rest in the defamation area and to have a clearly defined majority position that eliminates the unsureness engendered by Rosenbloom's diversity.” Powell shared concern that allowing each state to decide media liability for themselves may have some adverse effects, he ultimately concluded that “[w]hat the Court has done, I believe, will have little, if any, practical effect on the functioning of responsible journalism.”

Dissenting Opinion by Justice Douglas

In his dissenting opinion, Justice William Douglas argued against the imposition of state-defined standards of liability for defamation, emphasizing that any form of government-imposed liability, even for statements made about private individuals, inherently chills free expression. Describing the role of the Court in this case, he wrote, “I would suggest that the struggle is a quite hopeless one, for, in light of the command of the First Amendment, no ‘accommodation’ of its freedoms can be ‘proper’ except those made by the Framers themselves.” Douglas also underscored the fundamental importance of protecting all forms of speech, including those that might be erroneous, viewing such protection as essential to the vibrant discourse democracy requires. Douglas posited that the risk of defamation is a necessary cost of ensuring a free and uninhibited press, warning against the dangers of allowing state interests, even those aimed at protecting individuals from harm, to encroach upon the protections of the First Amendment. He believed that the Court's decision to allow states to set their own standards for defamation liability, especially when it concerns private individuals, represented a retreat from the robust protection of speech and press freedoms that the Court historically provided.