Miller v. California

Case Overview

CITATION

413 U.S. 15 (1973)

ARGUED ON

January 18-19,1972

REARGUED ON

November 7, 1972

DECIDED ON

June 21, 1973

DECIDED BY

Legal Issue

Does a conviction for the sale and distribution of obscene material through the mail violate the First Amendment’s protection of the right to free speech?

Holding

No, obscenity is not a form of protected speech under the First Amendment and should be judged by “community standards.”

Summary

5 - 4 decision for California

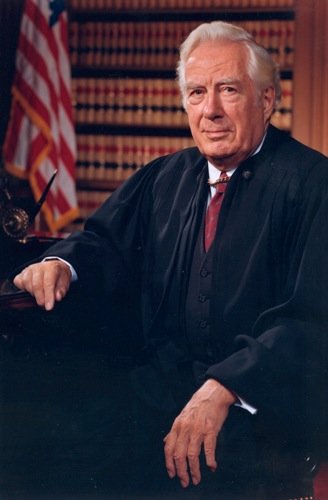

Burger

Douglas

Stewart

White

Blackmun

Brennan

Powell

Rehnquist

Marshall

Miller

California

An adult entertainment store | Credit: Getty Images

Background

In response to the Supreme Court’s decisions in Roth v. United States (1957) and Memoirs v. Massachusetts (1966), lawmakers in California enacted section 311.2(a) to the state’s Penal Code, which in part stated the following:

“Every person who knowingly sends or causes to be sent, or brings or causes to be brought, into this state for sale or distribution, or in this state possesses, prepares, publishes, produces, or prints, with intent to distribute or to exhibit to others, or who offers to distribute, distributes, or exhibits to others, any obscene matter is for a first offense, guilty of a misdemeanor.”

Marvin Miller owned and operated a mail-order business that sold pornographic materials, such as books and movies. In 1971, Miller mass-mailed a brochure showcasing his products with depictions of graphic sexual interactions between individuals. Among the recipients of these brochures were the owner and his mother of a restaurant based in Newport Beach, California. After unexpectedly receiving the graphic content, the owner alerted the authorities and Miller was arrested for violating California Penal Code 311.2(a).

Miller’s trial was held in the Superior Court of Orange County. The judge directed the jury to assess the evidence against Miller based on the prevailing community standards in the state of California, as stipulated by the law. The jury, after deliberation, delivered a verdict of guilty against Miller. On appeal to the Appellate Division of the Superior Court, Miller argued that the jury instructions deviated from the criteria established in the precedent of Memoirs, which required that materials deemed obscene must utterly lack any societal value. The Appellate Division dismissed this contention and affirmed the initial verdict reached by the jury. Miller then appealed on First Amendment grounds, and the Supreme Court granted certiorari.

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Chief Justice Warren Burger explained that while he ruled in favor of Miller, it was only because California’s statute was too broad. Miller argued that under the Court’s past ruling in Memoirs, which stated that obscenity included only material that was proven to be “utterly without redeeming social value,” his conviction could not stand. Burger rejected that argument and disagreed with the Court’s plurality opinion in Memoirs. He described the Memoirs standard as “a burden virtually impossible to discharge under our criminal standards of proof” and proceeded to establish a clear set of standards to be employed in judging obscene speech. He also noted that regulatory schemes surrounding the issue are still the responsibility of the legislature to determine.

Burger reaffirmed the authority of states to regulate obscene material “when the mode of dissemination carries with it a significant danger of offending the sensibilities of unwilling recipients or of exposure to juveniles.” In pursuit of these goals, however, Burger narrowed the scope of permissible regulations to only include works that depict or describe sexual conduct, which must be specifically defined in the regulation. Burger then explained the basic guidelines for examining obscenity must be:

Whether the average person, applying contemporary community standards would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest.

Whether the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law.

Whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.

Burger concluded with an emphasis on the importance of using community standards in judging obscenity instead of a universal national standard. He wrote, “[t]hese are essentially questions of fact, and our Nation is simply too big and too diverse for this Court to reasonably expect that such standards could be articulated for all 50 States in a single formulation, even assuming the prerequisite consensus exists.” Expecting states to conform to national standards of obscenity, he elaborated, was an “exercise in futility.” He also noted that the historical record does not provide any evidence that restrictions on obscene speech stifled any expression of literary, artistic, political, or scientific ideas.

Dissenting Opinion by Justice Douglas

In his dissenting opinion, Justice William Douglas reviewed the Court’s conflicting case law on the issue of obscenity and explained why the Court cannot develop a singular standard. Douglas described attempts at defining obscenity as “hodge-podge” and stated that “[t]o send men to jail for violating standards they cannot understand, construe, and apply is a monstrous thing to do in a Nation dedicated to fair trials and due process.” Douglas argued that since obscenity was not written into the Constitution, a constitutional amendment would be needed to define it. He wrote, “[i]f it [obscenity] is to be defined, let the people debate and decide by a constitutional amendment what they want to ban as obscene and what standards they want the legislatures and the courts to apply.”

Douglas strongly disagreed with the Court’s proposed guidelines for obscenity, explaining that while well-intentioned, it is not the job of the Court to establish new definitions. “What causes one person to boil up in rage over one pamphlet or movie may reflect only his neurosis, not shared by others. We deal here with a regime of censorship…” He also explained that just because obscenity is not a form of protected speech does not mean that the government may participate in the wanton restriction of such speech, writing “[t]he idea that the First Amendment permits government to ban publications that are ‘offensive’ to some people puts an ominous gloss on freedom of the press. . . No greater leveler of speech or literature has ever been designed. To give the power to the censor, as we do today, is to make a sharp and radical break with the traditions of a free society.”

Dissenting Opinion by Justice Brennan

In his brief dissent, Justice Brennan cited his opinion in Paris Adult Theatre I v. Slaton (1973), a similar case in which he held that a state statute restricting an adult theatre from playing obscene films was unconstitutionally broad and invalid on its face. He concluded that the case should be remanded to the lower court for further proceedings “not inconsistent with this opinion.”