Roth v. United States

Case Overview

CITATION

354 U.S. 476 (1957)

ARGUED ON

April 22, 1957

DECIDED ON

June 24, 1957

DECIDED BY

SUPERSEDED BY

Miller v. California (1973)

Legal Issue

Do federal and state statutes that prohibit the sale or distribution of obscene material through the mail violate the First Amendment?

Holding

No, obscenity is not a form of protected speech under the First Amendment. Federal and state laws prohibiting the sale or distribution of such material are not offensive to the Constitution.

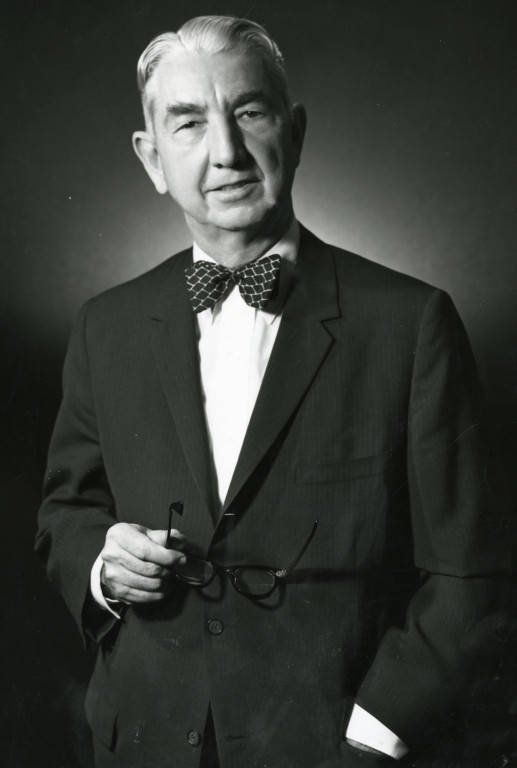

Roth testifying before the Senate on the effect of porn on juvenile delinquency. | Credit: The Associated Press, JH

Background

Laws restricting the sale or distribution of obscene materials have existed since the early nineteenth century, but until 1957, the Supreme Court had never considered the implications they may have on the First Amendment.

In New York City, Samuel Roth ran a book store in which he sold adult-books, many of which included erotica and nude photography. Roth was convicted under the federal statute 18 U. S. C. § 1461, which made it illegal to send obscene materials through the mail. A jury found him guilty of the charges.

Roth’s case was combined with the case of David Alberts, a California man charged under a state statute for selling lewd and obscene books. While Roth’s case decided if the federal government could prohibit obscenity, Alberts decided the same question on a state level.

Summary

6 - 3 decision for the United States

Roth

United States

Warren

Black

Frankfurter

Burton

Brennan

Clark

Whittaker

Harlan

Douglas

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Justice William Brennan upheld the convictions of both Roth and Alberts. Brennan established that the Court’s task was to determine the constitutionality of obscene speech under the First Amendment’s protections of speech and press. Brennan acknowledged that the First Amendment’s protections are not absolute, pointing to utterances such as libel that have long been considered outside the realm of freedom of speech. He did, however, cite the Court’s decision in Thornhill v. Alabama (1940) to note that on matters of public concern, members of the public must be allowed to “publicly and truthfully” discuss them without “previous restraint or fear of subsequent punishment.” Brennan established that while the government may impose restrictions on speech, they must be narrowly tailored to achieve a government interest.

With an understanding that the First Amendment is not absolute, Brennan turned towards a historical analysis to examine the role of obscenity laws in our nation’s history. Brennan argued that obscenity laws have been in use since before our country’s independence, pointing to examples such as Massachusetts’ 1712 law that made it a crime to publish “any ‘filthy, obscene, or profane song, pamphlet, libel or mock sermon’ in imitation or mimicking of religious services.” Brennan also cited the Court’s decision in Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942), in which they held that “[i]t has been well observed that such [lewd and obscene] utterances are no essential part of any exposition of ideas, and are of such slight social value as a step to truth that any benefit that may be derived from them is clearly outweighed by the social interest in order and morality.”

While he acknowledged the government’s interest in restricting obscene material, Brennan explained that “[t]he portrayal of sex, e. g., in art, literature and scientific works is not itself sufficient reason to deny material the constitutional protection of freedom of speech and press.” To judge obscene material in a consistent manner, Brennan established the prurient interest test, which examines obscene material by determining “[w]hether to the average person, applying contemporary community standards, the dominant theme of the material taken as a whole appeals to prurient interest.” Brennan understood that there is no precise way for the Court to take on the issues raised with regulating obscenity, but he stated that “lack of precision is not itself offensive to the requirements of due process.” Brennan ultimately concluded that both the federal statute and California’s statute were not offensive to the Constitution, therefore upholding Roth and Alberts’ convictions.

“The fundamental freedoms of speech and press have contributed greatly to the development and well-being of our free society and are indispensable to its continued growth. Ceaseless vigilance is the watchword to prevent their erosion by Congress or by the States. The door barring federal and state intrusion into this area cannot be left ajar; it must be kept tightly closed and opened only the slightest crack necessary to prevent encroachment upon more important interests.”

—Justice William Brennan

Concurring Opinion by Chief Justice Warren

In his brief concurrence, Chief Justice Earl Warren explained that while he agreed with the Court’s decision, he wrote separately “because broad language used here may eventually be applied to the arts and sciences and freedom of communication generally, [and] I would limit our decision to the facts before us and to the validity of the statutes in question as applied.” Warren acknowledged the enactment of obscenity laws by every state legislature and Congress demonstrated strong public support for obscenity laws, but he also noted the historic nature of their ability to create public controversy. He explained this concern, warning that “[m]istakes of the past prove that there is a strong countervailing interest to be considered in the freedoms guaranteed by the First and Fourteenth Amendments.”

Warren ultimately concluded by arguing for a different standard to be used when judging obscenity. Instead of establishing a test for the Court to judge obscene material, Warren argued that the Court should focus on the conduct of the defendant. He wrote, “The conduct of the defendant is the central issue, not the obscenity of a book or picture. The nature of the materials is, of course, relevant as an attribute of the defendant's conduct, but the materials are thus placed in context from which they draw color and character.”

Dissenting Opinion by Justice Harlan II

In his dissent, Justice John Marshall Harlan II posited that the Court’s depiction of obscene material was too far-reaching in its potential applications, writing “I am very much afraid that the broad manner in which the Court has decided these cases will tend to obscure the peculiar responsibilities resting on state and federal courts in this field and encourage them to rely on easy labeling and jury verdicts as a substitute for facing up to the tough individual problems of constitutional judgment involved in every obscenity case.” Harlan was concerned that the Court’s guidelines would lead judges to make independent judgements on the obscenity of materials instead of the “sensitive and delicate” constitutional review they require.

Harlan upheld Alberts’ conviction under California’s obscenity statute but found the federal statute used to convict Roth to be unconstitutional under the First Amendment. He explained that in our system of government, power is shared between the federal and state level governments. Harlan argued that the regulation of morality is the sole job of the states, not the federal government. He wrote, “Congress has no substantive power over sexual morality. Such powers as the Federal Government has in this field are but incidental to its other powers, here the postal power, and are not of the same nature as those possessed by the States, which bear direct responsibility for the protection of the local moral fabric.”

The interest shared by both the federal government and state government of California were stated as protecting the nation from pornography. Harlan accepted the interest as legitimate in Alberts, but he rejected the same argument from the federal government. Harlan argued that obscenity bans on a state level are permissible, as they have a limited effect on speech and because materials are still usually available in neighboring states. This system allows individual state legislatures to operate as “experimental social laboratories” that respond to their citizens’ demands. On the federal level, however, Harlan feared allowing them to ban materials nationwide, writing that “[n]ot only is the federal interest in protecting the Nation against pornography attenuated, but the dangers of federal censorship in this field are far greater than anything the States may do.” Harlan concluded that the Court’s blanket determination that obscenity is not protected speech is flawed and warned against the dangers of censorship.

Dissenting Opinion by Justice Douglas

In his dissent, Justice William Douglas rejected the Court’s prurient interest test, believing it to be far too broad and potentially chilling to speech. Douglas saw the decision as a step towards censorship, writing that “[a]ny test that turns on what is offensive to the community's standards is too loose, too capricious, too destructive of freedom of expression to be squared with the First Amendment. Under that test, juries can censor, suppress, and punish what they don't like, provided the matter relates to ‘sexual impurity’ or has a tendency ‘to excite lustful thoughts.’ This is community censorship in one of its worst forms.”

Douglas warned against the imposition of punishment for private thoughts and believed that “[t]o allow the State to step in and punish mere speech or publication that the judge or the jury thinks has an undesirable impact on thoughts but that is not shown to be a part of unlawful action is drastically to curtail the First Amendment.” He argued that this was far outside the government’s intended role and that laws should focus on anti-social behaviors instead. Douglas also warned against those who would lower the standards for speech to be considered impermissible that “the test that suppresses a cheap tract today can suppress a literary gem tomorrow. All it need do is to incite a lascivious thought or arouse a lustful desire. The list of books that judges or juries can place in that category is endless.” He concluded that decisions concerning obscene materials should be left to the people, not elected officials.