Ballew v. Georgia

Case Overview

CITATION

435 U.S. 223 (1978)

ARGUED ON

November 1, 1977

DECIDED ON

March 21, 1978

DECIDED BY

Legal Issue

Does a trial with a five-member jury deprive the defendant of the right to trial by jury guaranteed by the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments?

Holding

Yes, a trial by jury of less than six members violates the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments.

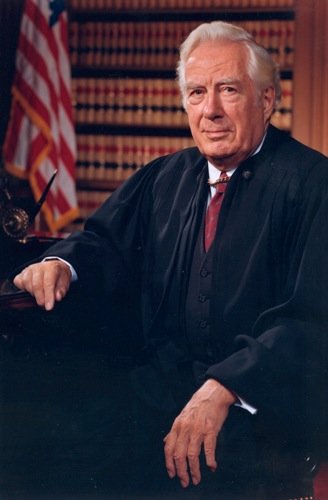

The Paris Adult Theatre in Fulton County, Georgia | Credit: Vincent Astor

Background

On November 9, 1973, two investigators viewed the movie “Behind the Green Door” at the Paris Adult Theatre in Fulton County, Georgia. After they viewed the film, they obtained a search warrant for its seizure and returned to the theatre on November 26, where they also watched the film again. The next day, the investigators went back to the theatre, viewed the film again, and seized a second copy of it.

On September 14, 1974, Claude Davis Ballew, the manager of the theatre, was charged with distributing obscene materials in violation of Georgia Code Section 26-2101. Ballew was tried before the Criminal Court of Fulton County before a jury of five members. Ballew filed a motion for the court to impanel a twelve-member jury, but the court overruled. After 38 minutes of deliberation, the jury found Ballew guilty and sentenced him to jail until he paid a $1,000 fine on each count. The trial court denied his motion for rehearing, and the Court of Appeals of the State of Georgia subsequently rejected his appeal. After the Supreme Court of Georgia denied his appeal, the U.S. Supreme Court granted certiorari.

Summary

Unanimous decision for Ballew

Ballew

Georgia

Burger

Douglas

Blackmun

Brennan

White

Stewart

Marshall

Powell

Rehnquist

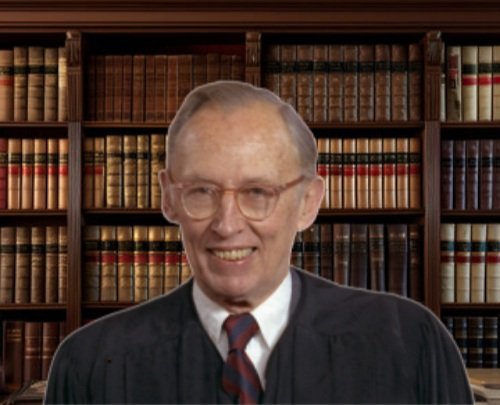

Opinion of Justice Blackmun

While the Court was extremely divided in their rulings, they unanimously concurred that a criminal conviction based on a jury of less than six members is unconstitutional.

In his opinion, Justice Harry Blackmun held that a criminal trial to a jury of less than six members substantially threatened the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments. In response to the lower court’s reliance on Williams v. Florida (1970), Blackmun noted that the Court’s holding that case “expressly reserved ruling on the issue whether a number smaller than six passed constitutional scrutiny.” He explained that while the Court was not prepared then to speculate on what, if any, number of jurors the Constitution required, they were now forced to. Writing for a divided Court/joined by Justice John Paul Stevens, Blackmun held that

Blackmun pointed out that juries with memberships of less than five face several issues avoided by a larger group. He argued that the smaller the group, the fewer individual members are able to overcome their personal biases, the fewer members will remember specific pieces of evidence, and members are less likely to provide critical contributions to solving the problem. In addition, he noted studies that found that the risk of convicting an innocent person rose as jury size decreased and expressed concern that the shrinking size of juries would proportionately exclude minority participation. In larger groups, however, Blackmun argued that members are more motivated to find an accurate solution and be self-critical of their work. Explaining his concerns, he wrote, “[w]e readily admit that we do not pretend to discern a clear line between six members and five. But the assembled data raise substantial doubt about the reliability and appropriate representation of panels smaller than six. Because of the fundamental importance of the jury trial to the American system of criminal justice, any further reduction that promotes inaccurate and possibly biased decisionmaking, that causes untoward differences in verdicts, and that prevents juries from truly representing their communities, attains constitutional significance.”

Responding to Georgia’s argument that a five-member jury was acceptable so long as the defendant was facing a misdemeanor charge, Blackmun cited the Court’s ruling in Baldwin v. New York (1970), which held that the right to a jury applied in both felony and misdemeanor cases. He explained, “[w]e cannot conclude that there is less need for the imposition and the direction of the sense of the community in this case than when the State has chosen to label an offense a felony. The need for an effective jury here must be judged by the same standards announced and applied in Williams v. Florida [1970].” Blackmun concluded that “the purpose and functioning of the jury in a criminal trial is seriously impaired, and to a constitutional degree, by a reduction in size to below six members.”

Opinion of Justice Brennan

In his brief opinion, Justice William Brennan explained that while he joined Justice Blackmun’s holding to require juries in criminal trials to contain more than five persons, he didn’t agree that Ballew could be subjected to a new trial, “since I continue to adhere to my belief that Ga. Code Ann. § 26-2101 (1972) is overbroad and therefore facially unconstitutional.”

Opinion of Justice White

In his brief opinion, Justice Byron White agreed with Blackmun’s judgment of reversal, but concluded that “a jury of fewer than six persons would fail to represent the sense of the community and hence not satisfy the fair cross-section requirement of the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments.”

Opinion of Justice Powell

In his brief opinion, Justice Lewis Powell agreed with the ruling that the use of a jury as small as five members to convict a defendant of a serious offense involved serious questions of fundamental fairness. Powell expressed concern, however, on Justice Blackmun’s expansive use of statistical studies to support his opinion explaining that “the studies relied on merely represent unexamined findings of persons interested in the jury system.” He ultimately concluded that “because the opinion of Mr. Justice Blackmun today assumes full incorporation of the Sixth Amendment by the Fourteenth Amendment contrary to my view in Apodaca, I do not join it.”