Scott v. Illinois

Case Overview

CITATION

440 U.S. 367 (1979)

ARGUED ON

December 4, 1978

DECIDED ON

March 5, 1979

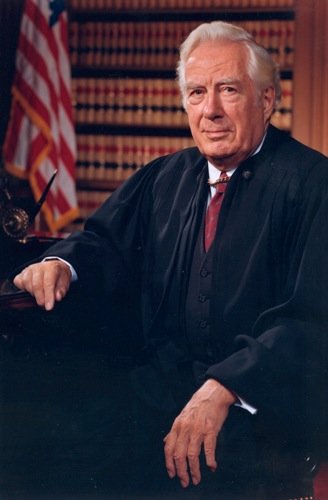

DECIDED BY

Legal Issue

Did the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments require Illinois to provide Scott with trial counsel given the facts of the case?

Holding

No, states can only sentence a defendant to imprisonment if they have been represented by counsel.

Cook County Circuit Court building in Chicago, Illinois | Credit: Stephen Hogan

Background

Curtis Scott was charged with shoplifting merchandise worth less than $150, classified as a petty theft under Illinois law. Despite the seemingly minor nature of the charge, the potential penalty for this offense included not only a fine but also the possibility of imprisonment. However, Scott was tried without the assistance of counsel and ultimately convicted solely to a fine, not imprisonment, which brought into question the application of the Sixth Amendment's right to counsel.

Initially, Scott was tried and convicted in Illinois state court. He contended that his constitutional right to counsel was violated because he faced the possibility of incarceration. Under the prevailing interpretation following the decision in Argersinger v. Hamlin (1972), an indigent defendant was entitled to appointed counsel only if actually sentenced to imprisonment, not merely because the offense was punishable by imprisonment.

Scott appealed his conviction, arguing that the denial of counsel in his case, where imprisonment was a possible penalty, constituted a violation of his Sixth Amendment rights as applied to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment. The Illinois appellate courts upheld his conviction, maintaining that the Sixth Amendment did not require the state to provide counsel where the sentence did not ultimately include imprisonment.

Summary

5 - 4 decision for Illinois

Scott

Illinois

Burger

Stevens

Blackmun

Brennan

White

Stewart

Marshall

Powell

Rehnquist

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Justice William Rehnquist held that the constitutional right to counsel, as established in Argersinger v. Hamlin (1972), only applies in cases that result in actual imprisonment. Rehnquist wrote that “the central premise of Argersinger—that actual imprisonment is a penalty different in kind from fines or the mere threat of imprisonment—is eminently sound and warrants adoption of actual imprisonment as the line defining the constitutional right to appointment of counsel.”

Rehnquist explained, however, that extending the right to counsel to all cases where imprisonment is a possible but not actual outcome would impose an unpredictable burden on the states. He wrote, “Argersinger has proved reasonably workable, whereas any extension would create confusion and impose unpredictable, but necessarily substantial, costs on 50 quite diverse States.” Rehnquist ultimately held that the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments require the provision of counsel only when the defendant is actually sentenced to imprisonment, upholding Scott's conviction without appointed counsel because he was not sentenced to jail time.

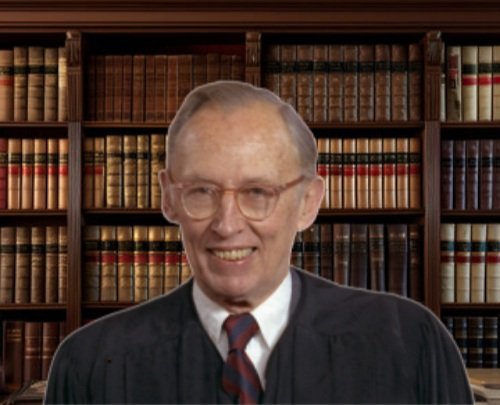

Concurring Opinion by Justice Powell

In his brief concurrence, Justice Lewis Powell an outlined several issues he viewed in the Argersinger decision. Brennan noted that “the drawing of a line based on whether there is imprisonment (even for overnight) can have the practical effect of precluding provision of counsel in other types of cases in which conviction can have more serious consequences.” He also explained that under Argersinger judges may forgo the legislatively granted option to impose a sentence of imprisonment because of difficulties obtaining counsel, especially in congested urban courts.

Ultimately, however, Powell joined the Court’s opinion because he believed it important that they “provide clear guidance to the hundreds of courts across the country that confront this problem daily.” He explained that he did so “with the hope that in due time a majority will recognize that a more flexible rule is consistent with due process and will better serve the cause of justice.”

Dissenting Opinion by Justice Brennan

In his dissenting opinion, Justice William Brennan argued against the majority’s decision to limit the right to counsel only to cases that result in actual imprisonment. He instead argued that the Sixth Amendment, as applied through the Fourteenth Amendment, should guarantee the right to counsel for any defendant facing a charge that carries a potential penalty of imprisonment, regardless of whether imprisonment is ultimately imposed.

Brennan criticized the majority for ignoring the fundamental principles established in previous landmark decisions such as Gideon v. Wainwright (1963) and Argersinger v. Hamlin (1972), emphasizing that the right to counsel is essential for ensuring a fair trial and that this right should not depend on the outcome of the trial but on the severity of the charges faced by the defendant. Brennan argued that “the right to counsel is more fundamentally related to the fairness of criminal prosecutions than the right to jury trial.”

Brennan explained the inconsistency in the majority's approach, noting that it creates a paradox where defendants have a constitutional right to a jury trial for certain offenses but are denied the equally fundamental right to counsel. Brennan states, “It restricts the right to counsel, perhaps the most fundamental Sixth Amendment right, more narrowly than the admittedly less fundamental right to jury trial.”

Brennan also pointed out the practical difficulties and potential injustices arising from the majority’s decision, arguing that determining whether to provide counsel based on the likelihood of actual imprisonment leads to unequal treatment and undermines the integrity of the judicial system. He asserted that the “authorized imprisonment” standard, which considers the potential penalties rather than the actual sentence, would provide a clearer and more just criterion for the right to counsel. Ultimately, Brennan argued that the Constitution requires the appointment of counsel for any indigent defendant facing charges that could result in imprisonment, irrespective of the final sentence imposed.