Argersinger v. Hamlin

Case Overview

CITATION

407 U.S. 25 (1972)

ARGUED ON

December 6, 1971

REARGUED ON

February 28, 1972

DECIDED ON

June 12, 1972

DECIDED BY

Legal Issue

Can a criminal defendant be imprisoned if they were convicted without the assistance of counsel?

Holding

No, the Sixth Amendment requires that criminal defendants be provided counsel if they are facing potential imprisonment.

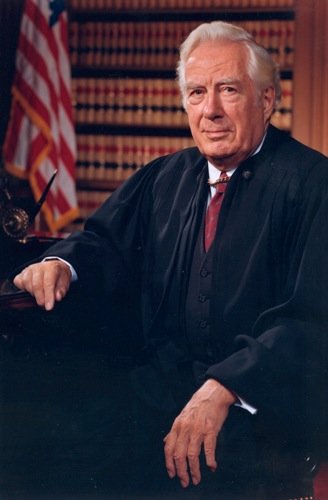

Leon County Sheriff Raymond Hamlin, the respondent in Argersinger v. Hamlin, photographed outside of the Tallahassee Airport (1975) | Credit: Donn Dughi via State Archives and Library of Florida

Background

Jon Argersinger was charged with carrying a concealed weapon, which was classified as a misdemeanor offense under Florida law. Although he faced a potential sentence that included imprisonment, Argersinger was tried without the assistance of counsel. At the conclusion of his trial, he was convicted and sentenced to serve a term of 90 days in jail. Argersinger, unable to afford an attorney, had not been provided one by the state, leading him to challenge the fairness of his trial on the grounds that his Sixth Amendment right to counsel had been violated.

Argersinger’s appeal was dismissed by the Florida Supreme Court, who cited the U.S. Supreme Court’s holding in Duncan v. Louisiana (1968), that jury trials were not required for crimes with a sentence of less than six months. The Florida Supreme Court argued that since jury trials were not required for such cases, then neither was counsel. Argersinger appealed again, and the U.S. Supreme Court granted certiorari.

Summary

Unanimous decision for Argersinger

Argersinger

Hamlin

Burger

Douglas

Blackmun

Brennan

White

Stewart

Marshall

Powell

Rehnquist

Opinion of the Court

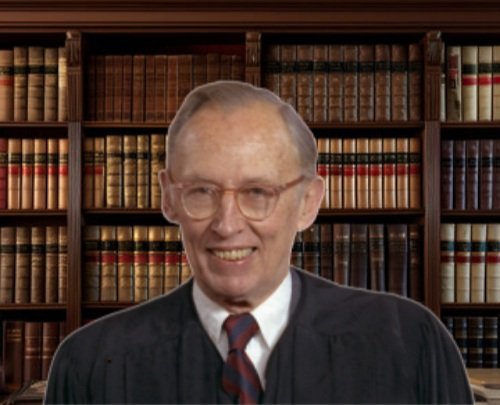

Writing for the Court, Justice William Douglas held that the Sixth Amendment's guarantee of the right to counsel was fundamental to a fair trial and applied to all criminal prosecutions, whether classified as felonies or misdemeanors. Douglas underscored the importance of the right to counsel in ensuring the fair administration of justice, stating that it, “is often a requisite to the very existence of a fair trial.”

Douglas rejected the premise that the right to counsel was limited to serious crimes. He pointed out that the right to a fair trial is compromised if an accused, regardless of the severity of the charge, is tried without the assistance of counsel. He instead argued that imprisonment, even for a brief period, is a serious deprivation of liberty and thus necessitates the appointment of counsel. Douglas emphasized that the Sixth Amendment’s right to counsel was essential for ensuring justice and fairness in all criminal prosecutions, reaffirming the Court’s rulings in Powell v. Alabama (1932) and Gideon v. Wainwright (1963). He explained that “Powell and Gideon suggest that there are certain fundamental rights applicable to all such criminal prosecutions,” and that the Court was “by no means convinced that legal and constitutional questions involved in a case that actually leads to imprisonment even for a brief period are any less complex than when a person can be sent off for six months or more.”

Douglas ultimately held that “absent a knowing and intelligent waiver, no person may be imprisoned for any offense, whether classified as petty, misdemeanor, or felony, unless he was represented by counsel at his trial.” He concluded, “[u]nder the rule we announce today, every judge will know when the trial of a misdemeanor starts that no imprisonment may be imposed, even though local law permits it, unless the accused is represented by counsel. He will have a measure of the seriousness and gravity of the offense and therefore know when to name a lawyer to represent the accused before the trial starts.”

Concurring Opinion by Justice Powell

In his concurring opinion, Justice Lewis Powell agreed with the Court’s holding but argued against the majority’s rule mandating the appointment of counsel for all indigent defendants facing imprisonment. Instead, he advocated for a more flexible, case-by-case determination to ensure fundamental fairness in trials, emphasizing that “due process, perhaps the most fundamental concept in our law, embodies principles of fairness rather than immutable line drawing as to every aspect of a criminal trial.”

Powell expressed concern over the practical implications of the majority’s decision, arguing that it could potentially strain already overburdened court systems and legal resources. He noted that in many petty offense cases, the costs of providing counsel might outweigh the benefits, especially where the likelihood of imprisonment is low or the evidence of guilt is overwhelming. Powell also pointed to the uneven distribution of legal resources across different jurisdictions, warning that the new rule could exacerbate existing inequalities in the legal system. Lastly, he expressed concern that a blanket rule might force judges to preemptively decide against imposing imprisonment, thus undermining the legislative intent behind certain penalties.

In his conclusion, Powell emphasized his “long-held conviction that the adversary system functions best and most fairly only when all parties are represented by competent counsel.” He concluded, however, that, “[t]he correct disposition of this case, therefore, has been a matter of considerable concern to me as it has to the other members of the Court. We are all strongly drawn to the ideal of extending the right to counsel, but I differ as to two fundamentals: what the Constitution requires, and the effect upon the criminal justice system, especially in the smaller cities and the thousands of police, municipal, and justice of the peace courts across the country.”

Concurring Opinion by Chief Justice Burger

In his concurring opinion, Chief Justice Warren Burger held that “[t]he issues that must be dealt with in a trial for a petty offense or a misdemeanor may often be simpler than those involved in a felony trial and yet be beyond the capability of a layman, especially when he is opposed by a law-trained prosecutor. There is little ground, therefore, to assume that a defendant, unaided by counsel, will be any more able adequately to defend himself against the lesser charges that may involve confinement than more serious charges.”

Burger acknowledged that the Court’s decision and others expanding the rights of criminal defendants may place additional burdens on the court system and legal profession, but he noted that “[p]art of this evolution has been expressed in the policy prescriptions of the legal profession itself, and the contributions of the organized bar and individual lawyers-such as those appointed to represent the indigent defendants in the Powell and Gideon cases have been notable. The holding of the Court today may well add large new burdens on a profession already overtaxed, but the dynamics of the profession have a way of rising to the burdens placed on it.

Concurring Opinion by Justice Brennan

In his brief concurrence, Justice William Brennan highlighted the important role that students in law school can play in easing the burden placed on an overworked court system. He highlighted several programs that already existed at law schools around the country and stated that “[g]iven the huge increase in law school enrollments over the past few years. . . I think it plain that law students can be expected to make a significant contribution, quantitatively and qualitatively, to the representation of the poor in many areas, including cases reached by today's decision.”